Sustainalytics: How Combining ESG Risk and Moat Ratings Can Benefit Portfolios

An overview of our recent report that looks at the relationship between ESG risk and moat ratings and, using back-testing, how portfolios based on the two ratings might have performed.

A growing body of evidence suggests that material environmental, social, and governance issues can have a significant impact on equity returns. If anything, this idea has gained further momentum in recent months, as the coronavirus pandemic has led more investors to consider ESG in their investment processes.

However, while assessing corporate ESG risks may be useful, it ultimately does not provide the full picture. There are many drivers of shareholder return that fall outside of a typical ESG assessment, including a company's approach to pricing, its mergers and acquisitions strategy, or its innovation pipeline. ESG factors can significantly influence these matters, but they have not yet become central to mainstream financial analysis. This is why portfolio managers who use ESG information typically blend it with other types of information in their investment process, such as traditional financial metrics or market price data.

Against this backdrop, in a new research report, Sustainalytics combines ESG Risk Ratings with Morningstar's Economic Moat Rating. This report looks at the relationship between ESG risk and moat ratings and, using back-testing, how portfolios based on the two ratings might have performed.

While the ESG Risk Ratings measure the unmanaged risks of a company in relation to a set of financially material ESG issues, Morningstar's Economic Moat Rating measures the durability of a company's competitive advantage and helps investors identify companies that are likely to generate excess returns on invested capital over 20 years or longer. Morningstar has defined five sources of economic moat: cost advantage, efficient scale, intangible assets, network effects, and switching costs.

Generally speaking, the research shows that the wider the moat and the lower the ESG risk, the higher the average return of the portfolio and the lower its volatility. Through back-testing a portfolio, the research found that combining economic moat and ESG Risk delivered superior results compared with each strategy individually.

Here’s an overview of the report’s findings:

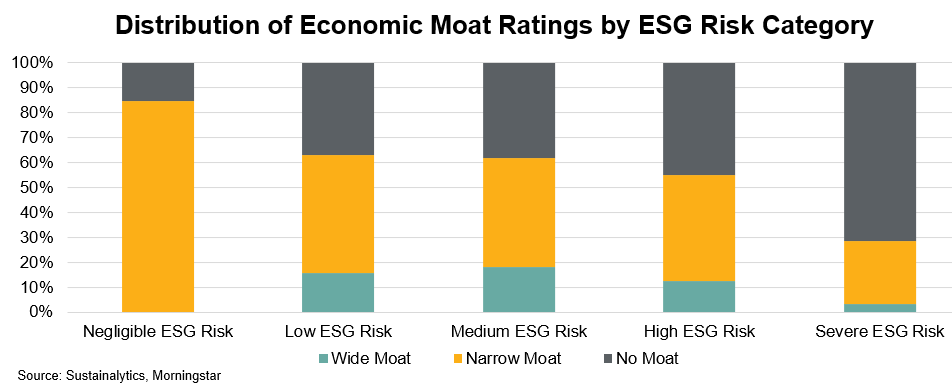

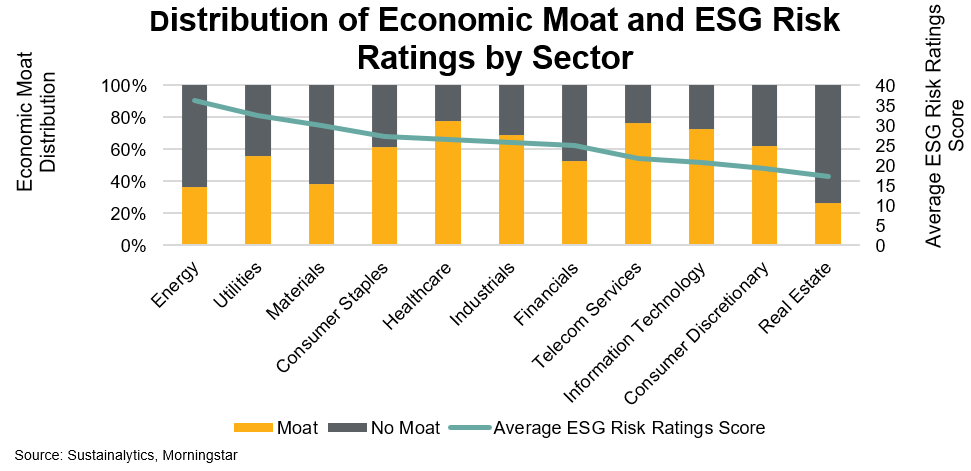

Moats tend to be less common at companies with High levels of ESG Risk. Looking at a cross-sectional analysis of ESG Risk and the Economic Moat Ratings within Morningstar’s research universe of 1,500 companies globally, we found these two variables negatively correlated: As one moves up the ESG Risk curve, moats become less frequent.

Only 3% of companies in the Severe ESG Risk bin have a wide moat while nearly half (48%) of companies in the Low ESG Risk bin have a narrow moat, and 16% have a wide moat. Examples include adidas AG, Cisco Systems, and Johnson Controls (narrow moat) and Microsoft, Hermes International, and Royal Bank of Canada (wide moat).

Looking at moat frequency and ESG risk by sector, energy is the riskiest sector from an ESG perspective. Of the 90 energy companies in Morningstar's coverage universe, only three--Core Laboratories, Cheniere Energy, and Enbridge--have a wide moat rating and a Medium ESG Risk Rating (there are no energy firms with a Negligible or Low ESG Risk Rating).

ESG risks and economic moats indeed seem to go hand in hand, based on both economic intuition and empirical evidence. However, does it also pay off to combine them in an investment strategy? Is there a good reason to assume that a strategy that seeks to select companies performing well in the Morningstar Economic Moat Rating and in the Sustainalytics' ESG Risk Ratings would outperform? Does overlaying an ESG signal on top of a moat signal (or vice versa) add any incremental value?

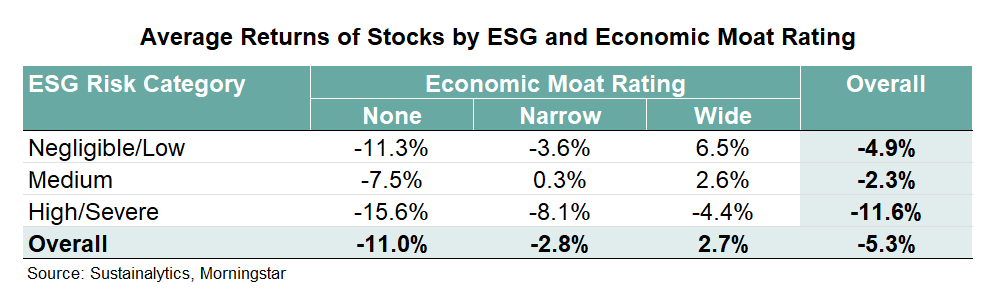

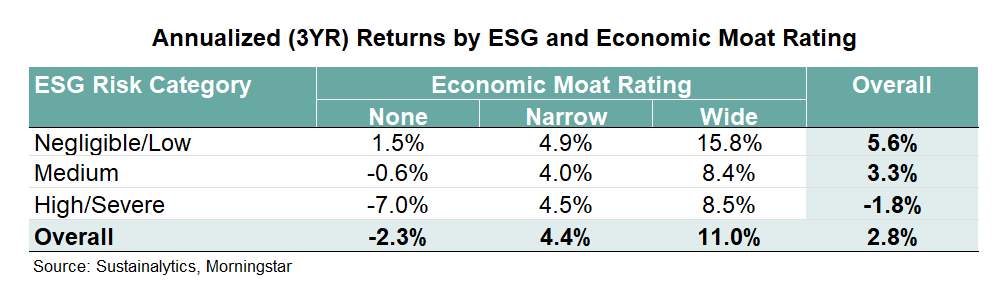

We approached this question in two ways. First, we looked at the year-to-date performance numbers to see how moat and ESG strategies played out during the COVID-19 sell-off and subsequent recovery. The general pattern appears to be: the wider the moat and the lower the ESG risk, the higher the return.

During the COVID-19 period, the highest return spread we found was delivered by comparing the lower-risk/wide-moat bucket with the higher-risk/no-moat bucket. The difference between the average returns of companies in these two buckets is 22.8%. Wide-moat and lower-ESG risk names include Microsoft, Adobe, Lam Research, Mastercard, Pernod Ricard SA, Home Depot, West Pharmaceutical Services, Sartorius Stedim Biotech SA, and Moody's. The combination also rules out entire sectors in the Sustainalytics taxonomy such as energy, telecommunications, real estate, and utilities.

Second, we tested the strategies over a more extended investment period stretching back to July 2017. For our tests, we looked only at those companies that remained in the same categories for both ESG Risk and economic moat since the launch of the Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings product in November 2018, providing us with a sample size of 799 companies.

Over the three-year period, Negligible/Low ESG Risk and wide-moat companies returned 55% to shareholders, while no-moat and High/Severe ESG Risk companies led to losses for investors of 20%.

While three years is too short a period to draw definitive conclusions, we can be sure that COVID-19 is not an exception for performance.

We conclude that the superior return characteristic of a lower ESG risk and wide-moat strategy are not limited to COVID-19 specific factors but have root causes that are more general in nature and are at work during different market regimes.

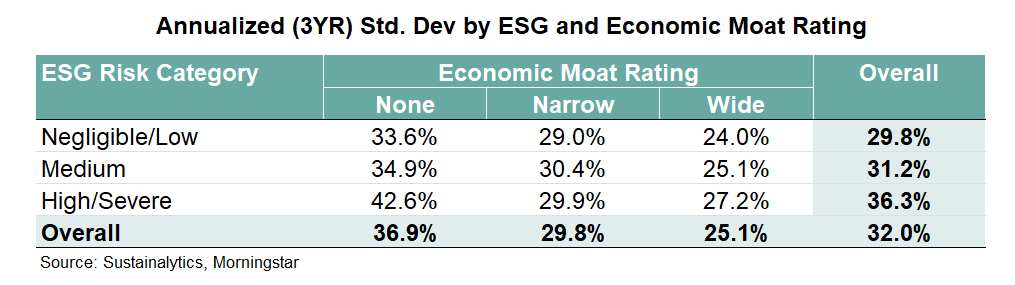

The assumption that more long-term, systematic forces seem to be at work is also supported by the clear pattern that emerged when we looked at investment risks over the same three-year period as represented by the volatility of monthly returns. The next table demonstrates that both ESG Risk and economic moat are clearly correlated with volatility following the intuitively expected pattern.

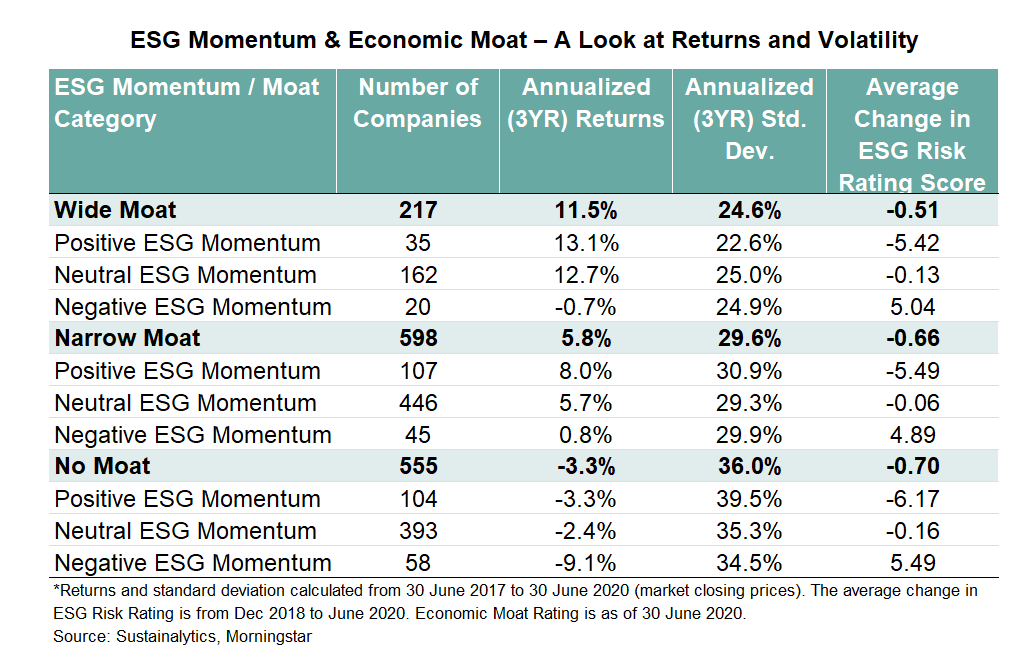

Prior research, however, suggests that identifying companies with improving ESG ratings may also deliver superior return and risk characteristics. We also analyzed the relationship between ESG Momentum and Economic Moat Ratings with regards to average returns and volatility for 1,340 companies out of our total sample of 1,500 companies.

We defined ESG momentum as follows:

- Positive--A decrease in ESG Risk score of 3.0 points or more;

- Negative--An increase in ESG Risk score of 3.0 points or more;

- Neutral--A change in ESG Risk score between -3.0 and +3.0.

Wide-moat companies with positive ESG momentum returned 13.1% per year, where companies with a wide moat and a negative ESG momentum saw a decrease of negative 0.7%.

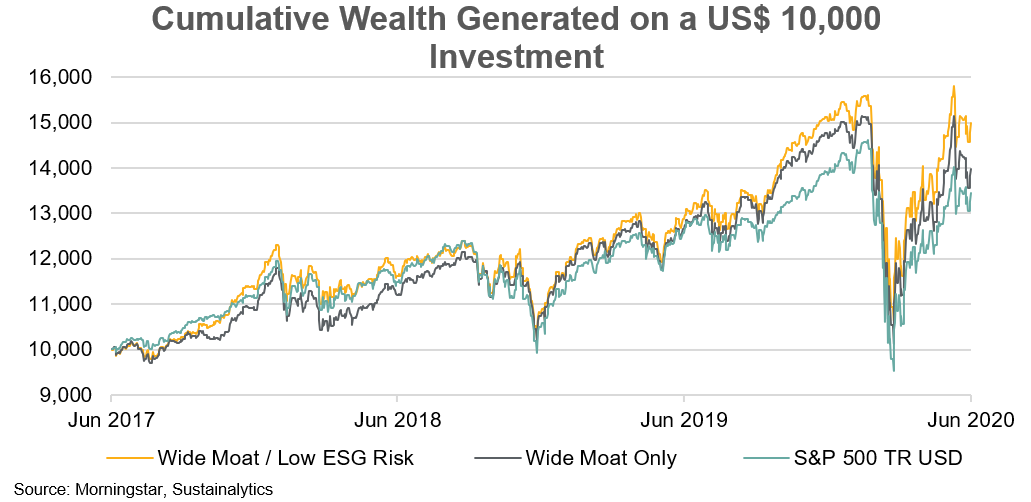

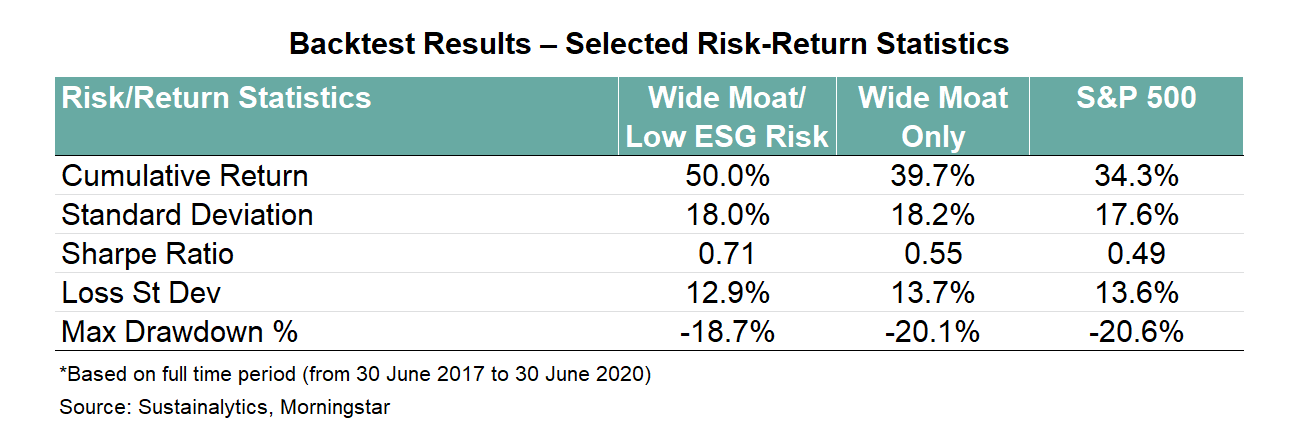

Given the evidence that Low ESG Risk and wide-moat companies have superior risk-return characteristics, we attempted to validate these findings by constructing a "real-world" index portfolio that takes both factors into account in portfolio construction. For this exercise, we used the Morningstar Wide Moat Focus TR USD Index as a blueprint and as a benchmark. The Morningstar Wide Moat Focus Index provides exposure to companies with Morningstar Economic Moat Ratings of wide that are trading at the lowest current market price/fair value ratios as determined by Morningstar’s analyst team. The S&P 500 TR USD served as the general market benchmark.

With this wide-moat/Low ESG Risk strategy for U.S. equities, we found a cumulative return of 50% over our three-year investment period, significantly outperforming the market as represented by the S&P 500 (34.3%) and a wide-moat-only strategy (39.7%).

All in all, our results are encouraging. Both metrics, ESG Risk and economic moat, work on a stand-alone basis as stock-selection criteria but even more successfully when combined.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TP6GAISC4JE65KVOI3YEE34HGU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RFJBWBYYTARXBNOTU6VL4VSE4Q.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YQGRDUDPP5HGHPGKP7VCZ7EQ4E.jpg)