Who Saved the U.S. Stock Market Last Spring?

The help came from an unexpected source.

Editor's note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what investors can do to navigate it.

Dry Powder It wasn't that long ago, yet it was also 10,000 Dow Jones points away. In late March, U.S. equities were reeling, having shed one third of their value over the previous five weeks. Then spring arrived--and boy, did it arrive. By August, the S&P 500 had fully recovered its losses. The broader market eventually followed suit, such that even Vanguard Small Cap Value Index VISVX is now in the black.

It seemed that U.S. households must have triggered the rally. Although COVID-19 quickly sidelined 15 million workers, few of the newly unemployed held stocks. Meanwhile, the well-heeled who possess most of the country's equities--the wealthiest 1% of U.S. households own slightly over half of all stocks and mutual fund shares-- prospered. Their income remained largely intact while their spending plummeted. Consequently, their cash piled up as never before.

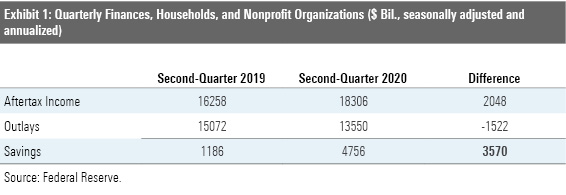

Consider the following data, provided by the Federal Reserve. It compares the after-tax income, outlays, and net savings for Households and Nonprofit Organizations--an odd combination, but as households account for 90% of the group's income the output is reasonably pure--for the two time periods of second-quarter 2019 and second-quarter 2020. The figures are annualized.

Talk about cash piling up! To be sure, half those additional savings came from The Cares Act payments, to working- and middle-class Americans who stashed the money away, waiting to pay future bills. Those monies would never be invested in the stock market. But much of the remaining savings went into the pockets of the investor class.

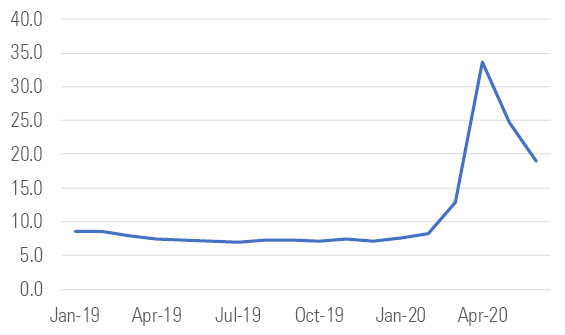

A picture illustrates the size of the effect. Exhibit 2 below depicts the monthly personal savings rate, derived by dividing that same net savings amount for Households and Nonprofit Organizations by that same after-tax income, from January 2019 through June 2020. As you will notice, the line makes more than a slight detour when April 2020 arrives.

Exhibit 2: Savings Rates, Household and Nonprofit Organizations (January 2019-June 2020)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

April 2020 was by far the highest personal savings rate posted since the Federal Reserve began tracking such figures, in 1959. At 33.7%, the month's total dwarfs the previous record's 17.4%, established in May 1975. As you may recall, during the 2000s there was much handwringing that the U.S. personal savings rate had become too low. Americans were grasshoppers rather than ants. Not so today.

Holding Out One might think that at least some of these excess assets leaked into the U.S. stock market. But they did not. The Federal Reserve reports that Households and Nonprofit Organizations decreased their direct equity holdings by $94 billion during second-quarter 2020. True, they did add $338 billion of mutual funds--but a quick check of Morningstar's database reveals that while bond and money-market shares received inflows, U.S. equity funds suffered net redemptions.

Thus, while the combination of emergency federal disbursements plus reduced spending fattened consumers’ wallets, and would seem to have fueled the stock market’s recovery when those who did not need those assets put them to work, such was not the case--at least during the ferocious second-quarter rally. (Whether those monies later found their way into American equities is a question that awaits further data releases.) The inflows came from elsewhere.

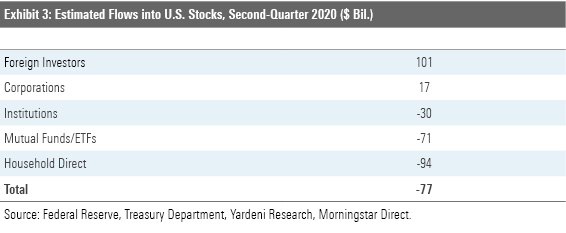

Other Pockets That elsewhere consists of three possibilities: 1) institutional investors, 2) foreigners, and 3) corporations, through share-repurchase programs.

The actions of institutional investors are difficult to measure. They come from several sources, including pension funds, insurance pools, and nonprofit funds (which, as we saw, the Federal Reverse unhelpfully groups with households). They might hold equities directly, or through investments that are largely designed for institutions, such as private-equity or hedge funds. Or they might invest alongside individual buyers, in registered mutual funds or exchange-traded funds.

Fortunately, Yardeni Research has done the work. The company estimates that U.S. institutional investors also sold domestic stocks during the second quarter. This was no surprise, as, inspired by the Yale Model, institutions have been gradually reallocating from domestic equities throughout the past decade. Their second-quarter outflows were, in fact, remarkably steady, almost exactly matching those of the previous several quarters.

The Treasury Department monitors the actions of foreigners who invest in U.S. securities. According to its figures--which, once again, are imperfect, as (for example) an offshore fund that technically qualifies as a foreign investor may possess domestic shareholders--foreign investors purchased a net $101 billion of U.S. equities during this year’s second quarter. They were particularly active in May, registering their highest-ever inflows.

Rounding out the troika were corporations. Normally, they are among the most-aggressive buyers of U.S. stocks, investing about $125 billion per quarter, with roughly that amount of new issuance more than counterbalanced by large stock-buyback programs. However, the corporations reduced their repurchases during the second quarter, while increasing their new issuance, thereby slashing their net investment to a modest $17 billion.

Wrapping Up Assembling the numbers leads to the final table.

The total cannot be correct. Each dollar that enters the marketplace must exit through another door, leading to a final amount of zero. Such is the uncertainty associated with collecting data from different sources. The fund-flow information is particularly tricky, because we don’t know if those trades were made by retail investors or institutions. If those net sales came entirely from institutions, then the figures would sum to negative 6, which is very close to the desired result of zero.

However, those sales almost certainly did not come solely from institutions, meaning that the error term is larger than one would hope. However, that doesn’t change the general finding. No matter how one adjusts the numbers, there’s no escaping the conclusion that, despite being awash in cash, U.S. households did not come to the market’s rescue. For that action, American investors depended on the kindness of strangers.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)