Back to School? How the Coronavirus Could Shape the Future of Higher Education

The pandemic has made students and families reconsider the true value of a college education.

When the novel coronavirus emerged in the United States early this year, colleges had to act quickly: They closed dorms, canceled sports seasons, and implemented online courses wherever possible.

These steps were imperative in the short term, but when it became clear that efforts to contain the pandemic would be a marathon, not a sprint, colleges had to reassess what a longer-term solution to maintaining enrollment numbers in the midst of a pandemic could look like.

And the question of how to tackle this issue underscores the institutions' competing concerns--for one, balancing their need for income from tuition with students and their families' reservations about paying full price for online or hybrid instruction.

While many students and families are concerned that the online experience isn't as valuable--according to The New York Times, about one fifth of Harvard University's incoming freshman class opted to defer admission rather than spend part of the year online--many colleges are arguing that their costs have not decreased.

In fact, they may have even increased owing to the cost of:

- scaling up online learning efforts (such as purchasing additional licenses for online instruction platforms, like Zoom Video Communications),

- retrofitting campus buildings and dormitories to fulfill increased public health requirements, and

- hiring more teachers and offering more classes to allow for more physical space between students.

These heightened costs come alongside lost income from entities like dormitories, dining, and athletics programs.

These changes bring into focus the various pieces of the college experience and the value of each one. Ultimately, college students, families, and investors are left to ask themselves: What is the true value of a college education?

The Pandemic Is Pressuring an Increasingly Brittle Value Proposition The fact is, families had begun to question whether skyrocketing prices for higher education were worth it long before the pandemic hit--and the coronavirus is amplifying those questions.

"The coronavirus is forcing people to take a hard look at that $51,000 tuition they're spending," said Scott Galloway, a marketing professor at NYU's Stern School of Business in this New York Magazine article. "Even wealthy people just can't swallow the jagged pill of tuition if it doesn't involve getting to send their kids away for four years."

The College Board reports that the average cost of a year of tuition for the 2019-20 school year for an in-state student at a public university was more than $10,000; for private college, it was more than $36,000. It also estimated that room and board adds roughly $12,000 to those totals.

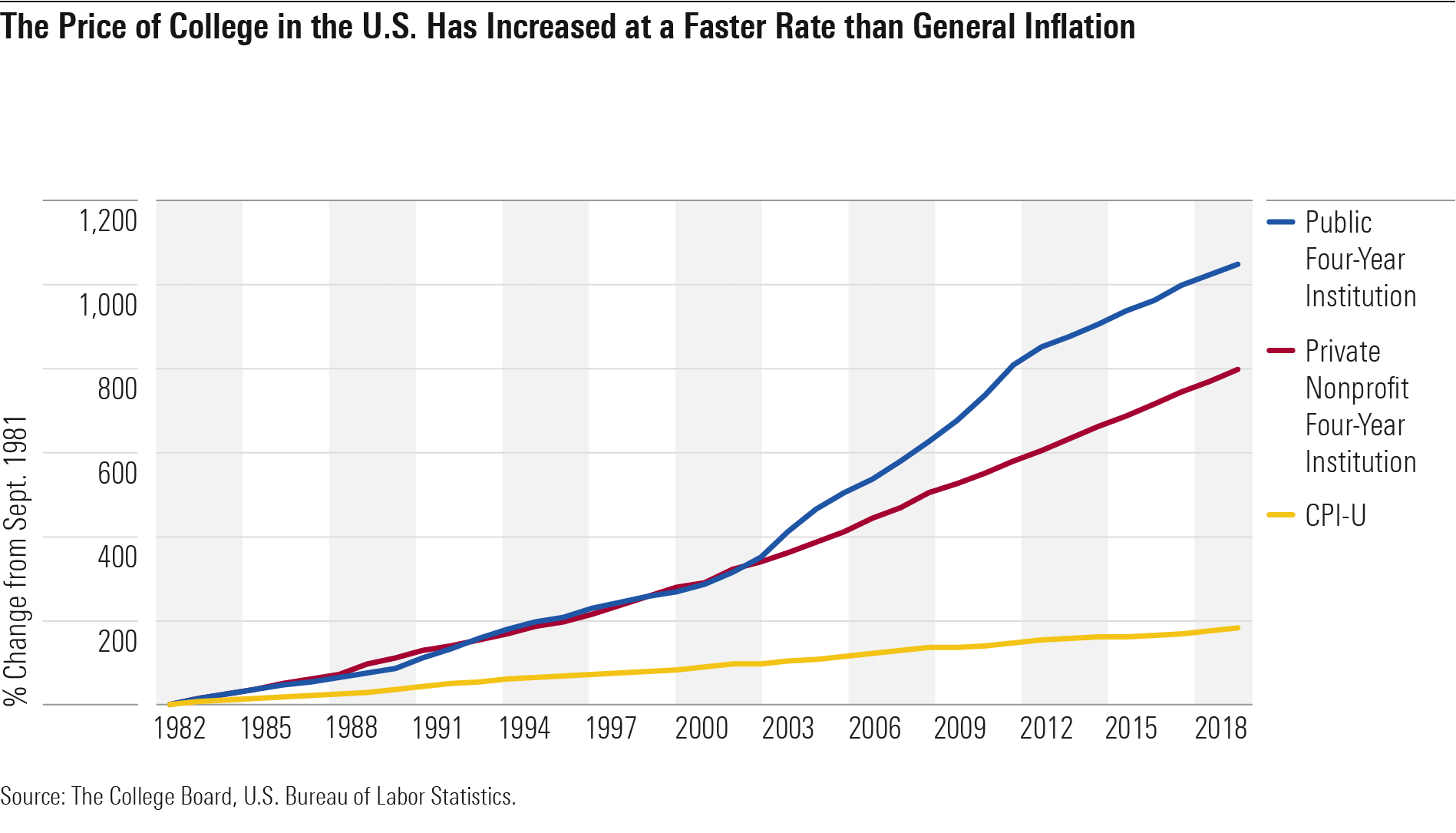

This price has been increasing at an extraordinarily steep rate over the past few decades. It has risen faster than overall inflation as calculated by the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Unsurprisingly, these ballooning costs have led to increased borrowing. In 2019, more than two thirds of bachelors' degree recipients graduated with an average of nearly $30,000 in student loans, according to Mark Kantrowitz of savingforcollege.com. Though some numbers seem to show that student loan borrowing is slowing, this actually reflects that more students are reaching the upper limits on federal student loans, which have also not kept pace with college tuition inflation. As a result, borrowing has shifted from students to parents, especially at higher-cost colleges, which isn't ideal for parents approaching or in retirement.

Does the Value of College Education Make the Cost 'Worth It'? The decades-old rationale for swallowing these costs has always been that they're "worth it" because a college graduate is likely to receive a higher salary over his or her career. Put simply, the price of higher education ought to be an investment in your human capital that will be recouped, with interest, over your lifetime.

But that logic also means that it's possible for the investment to be overvalued—in other words, it's possible to pay "too much" for college. When deciding how much a college degree is worth, as well as how much you should borrow and at what interest rate, it makes sense to consider the degree in the context of your expected earnings.

For instance, you could hamper your lifetime wealth-building potential by taking on too much debt to finance a degree if your post-graduation salary is not high enough. In the article "The College Question," Morningstar's Sarah Newcomb, David Blanchett, and Christine Benz note, "Researchers have followed the lives of thousands of people after graduation, tracking their financial circumstances and their ability to repay the debt as well as their feelings of burden and stress about the debt. The results show that most people are able to manage their school debt without much burden as long as they keep their payments below 8% of their pretax salary."

But this raises questions of fairness and equal opportunity, because it's low-income students who will be burdened with a level of debt that requires them to pay more than this threshold. A report from the Institute for Higher Education Policy explains that low-income students need to finance, on average, more than 100% of their family's annual income to attend one year at a four-year college, as compared with high-income students, who need to finance only 15% on average. "Education is crucial to [economic and social] mobility, yet high college costs are stymieing progress for Americans of limited financial means, undermining our basic ideals of opportunity and fairness," the report says.

Further, most people don't view the cost of college solely through the lens of recouping the cost of their investment. Beyond being an investment in human capital, college is also an experience. And it's balancing the value of both aspects that's at the heart of the cost debate.

For many people, being on campus and away from home is a key part of the college experience. It's a time of social awakening and discovery, of building networks and friendships. Alumni take pride in their alma mater; many go on to make regular charitable donations, support their college sports teams, and some even aim to send their children to that school as legacies.

Could an online degree program really take the place of that experience?

What Could Remote Learning Mean for the Future of Higher Education? Though corporations have been investing heavily for years in software to help overhaul manual or paper-based processes with digital ones--"going paperless" and "digital transformation" are examples of a shift to more efficient methods of working in the private sector--most colleges hadn't made as much progress with this effort when the pandemic hit.

Rather, in order to keep operating and remain productive during pandemic lockdowns, colleges were forced to rapidly implement software that facilitates online collaboration such as video conferencing, file sharing, and team chatting.

The costs of these sudden operational changes hit many colleges at a bad time: In March, credit rating agency Moody's downgraded its outlook for the higher education sector from stable to negative, saying that many universities' already-precarious financial condition makes them even more vulnerable to pandemic-related disruptions. Roughly 30% of the colleges and universities that Moody's tracks were operating with deficits before the pandemic hit, making it even tougher for them to adapt or invest as needed to survive the pandemic.

But amid the pandemic, colleges had to quickly embrace remote learning whether they were financially prepared to do so or not. Despite the short-term pain, overhauling costlier and less efficient operations and systems has the potential to benefit colleges and their students in the long term.

In Galloway's article, he predicts that in the future, partnerships between tech companies will help make it possible for colleges and universities to expand enrollment--perhaps dramatically--by offering hybrid online/in-person degrees. Though a hybrid or totally online degree is currently perceived by many to not be as valuable as a degree earned on campus, it's also substantially more affordable. Theoretically, a wider adoption of online learning among colleges and universities could democratize higher education by making it more affordable and more easily accessible.

And in that future, Galloway opines, colleges' brand strength and their ability to innovate and stay efficient will be key to their survival and success. He says, "There will be a dip, the mother of all V's, among the top-50 universities, where the revenues are hit in the short run and then technology will expand their enrollments and they will come back stronger. In 10 years, it's feasible to think that MIT doesn't welcome 1,000 freshmen to campus; it welcomes 10,000. What that means is the top-20 universities globally are going to become even stronger. What it also means is that universities Nos. 20 to 50 are fine. But Nos. 50 to 1,000 go out of business or become a shadow of themselves. I don't want to say that education is going to be reinvented, but it's going to be dramatically different."

How Can Investors Benefit from Colleges' Digital Transformation? Whether you subscribe to Galloway's outlook or not, the digital transformation will only continue for higher education. And smart investments in digital solutions have the potential to benefit colleges and universities: They can control cost inflation, enable institutions to operate more efficiently, and help students and faculty communicate more effectively.

I spoke to Dan Romanoff, a Morningstar equity research analyst who covers tech companies, to discuss his valuations and outlooks for some of the companies that specialize in software solutions for schools.

Zoom Video Communications ZM Morningstar Economic Moat Rating: None Fair Value Estimate (as of Sept. 30, 2020): $153.00 Zoom Video Communications is disrupting and expanding the $43 billion video conferencing market with its ease of use and superior user experience, in Romanoff's view. User growth has been phenomenal in recent quarters, especially during coronavirus-induced lockdowns, he notes. But while he sees some evidence of switching costs owing to Zoom's product and technology advantages, he doesn't yet have sufficient confidence in its ability to earn excess returns on capital over the next 10 years to warrant a narrow moat rating.

Zoom has executed well early in its life cycle by employing a "freemium" model (pricing tiers are based on a per user per month basis) and land-and-expand strategy, Romanoff says. That means that it does many small deals with vendors and works its way up to more substantial enterprise-level deals with larger customers.

Colleges use the company's core platform, Zoom Meetings, for purposes of individual and group video conferencing, screen sharing, audio conferencing, searchable and archived transcripts, chat, and file sharing. The company's other services and products include Zoom Rooms; Zoom Conference Room Connector (which allows organizations using legacy providers like Cisco to join Zoom meetings); Zoom Phone (the company's cloud-based phone system); and Zoom Video webinars.

Romanoff believes that the current valuation for Zoom courts risk and that investors should wait for a better entry point. While the company is expected to produce revenue growth at the high end of its peer group and the premium may be justified, higher valuations offer less room for missteps and therefore carry greater risk that the stock price will be punished severely if earnings do not meet or exceed expectations, he says.

Microsoft MSFT Morningstar Economic Moat Rating: Wide Fair Value Estimate (as of Sept. 30, 2020): $228.00 Microsoft is generally a partner to everybody, including schools, says Romanoff. Colleges and universities use Microsoft Office 365 for programs like Word and Excel, as well as collaboration features such as OneDrive for document sharing, Teams for chatting and video conferencing, and Outlook for email.

Romanoff assigns Microsoft a wide moat rating overall and believes the tech giant has three main segments and different products that benefit from different moat sources.

First is Microsoft's Productivity and Business Processes segment, which includes Office, Dynamics, and LinkedIn; it benefits from high switching costs and network effects.

Romanoff believes that Microsoft Office, including both 365 and the perpetual license version, is protected by a wide moat driven by high switching costs and network effects. Microsoft Office programs are widely used; they function well, and users are familiar with them. Many companies use Excel to help run critical business operations, for example; data can be pulled from Oracle, SQL, or other popular databases into an Excel file that can then be manipulated and analyzed further.

This leads to the other pillar underlying Office 365's moat: the network effect. A large installed base draws software developers to create products specifically for Microsoft Office. For example, Romanoff says, the financial community has created a wide variety of Excel add-ins in order to smoothly integrate popular platforms such as Factset, Bloomberg, and CapitalIQ, which helps attract and retain users to the software platform.

Microsoft's other two main segments, the Intelligent Cloud segment (which includes Windows Server, SQL Data Base Management System, Azure, Enterprise Services, and Visual Studio) and the "More Personal Computing" segment (which includes Windows, Gaming, Devices, and Search) earn wide and narrow moats, respectively.

Blackbaud BLKB Morningstar Economic Moat Rating: Wide Fair Value Estimate (as of Sept. 30, 2020): $70.00 Blackbaud makes software that colleges and universities (among other types of nonprofits) use to manage their fundraising and business operations. The leading software provider in the nonprofit market, Blackbaud offers its customers more essential end-to-end capabilities than competitors, in Romanoff's view. Its broad range of essential software is one of its competitive advantages: Blackbaud's programs include a searchable database of charitable donors, customer relationship management, campaign management, grant management, payment processing, fund accounting, and more.

The main reason Romanoff believes Blackbaud has a wide economic moat is high customer switching costs: Customers are hesitant to switch to a solution from a different software provider because the risk is simply too high that there would be business disruption, data loss, and lost productivity. Therefore, Blackbaud has a very high customer retention rate in the low to mid-90% range.

Romanoff does not expect to this to change: As the company navigates the switch from a perpetual license to a subscription model, it is focusing on adding sales reps and driving revenue. And he believes the market opportunity remains large. About 25% of charitable donations in 2019 were made on Blackbaud's platform. And with 1.6 million nonprofits in the U.S., and only 40,000 customers, Romanoff believes there is ample room for Blackbaud to grow its customer base.

Tyler Technologies TYL Morningstar Economic Moat Rating: Wide Fair Value Estimate (as of Sept. 30, 2020): $322.00 Tyler Technologies' software runs back-end systems that help cities, counties, schools, courts, and other local government entities run smoothly.

The company makes software solutions for the public sector that facilitate financial management, human resources, revenue management, tax billing, and asset management. And as the company has expanded its footprint and established its reputation for building intuitive operational solutions, it has become easier for Tyler to win business in the fragmented local public institutions market. That market has a lot of future growth potential, too, as many municipalities and public institutions are overdue to upgrade legacy software systems with newer, more efficient systems.

Romanoff assigns a wide moat rating to Tyler Technologies owing mainly to high customer switching costs. First, there are direct costs associated with replacing an existing software system. There are also indirect costs, such as lost productivity as employees are trained on the new system. But perhaps the most important risk, Romanoff says, is operational disruption. Given that Tyler provides the core systems that power critical functions for public institutions, he believes Tyler's customer retention rates will remain extremely high.

The company also derives a competitive advantage from its robust portfolio of software, which would be difficult for a startup, or even an established software vendor without government expertise, to replicate, Romanoff says.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/3a6abec7-a233-42a7-bcb0-b2efd54d751d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/3a6abec7-a233-42a7-bcb0-b2efd54d751d.jpg)