Why Preferred Stocks Don't Make Good Bond Substitutes

Their yields might look tempting, but they come with a few drawbacks.

It’s easy to see the appeal of preferred stocks as a potential bond substitute. The 10-year Treasury yield is now hovering around 0.7%, and the Federal Reserve has indicated that it plans to keep benchmark yields low for the foreseeable future. At the same time, inflation has shown early signs of edging up. Fixed-income investors therefore face the unappetizing prospect of losing money in real terms over the next few years.

Not surprisingly, investors have been digging under a lot of rocks in search of income. As John Rekenthaler wrote recently, preferred stocks have been one of the most popular areas being discussed as a bond substitute. The eminent Burton Malkiel spoke favorably about preferred stocks on Morningstar's The Long View podcast in August. John has covered some of the pros and cons already; in this article, I'll expand on some of the risks to be aware of.

Background Preferred stocks are a type of hybrid security, with a blend of equitylike and bondlike characteristics. Like bonds, preferreds make regular income payments and have a fixed par value. Unlike bonds, though, preferred stocks aren't guaranteed obligations and rank lower in the capital structure than traditional debt. In the event of a bankruptcy, bondholders take preference over preferred stockholders for receiving payment; preferred stock ranks below subordinated debt in the capital structure. Like stocks, preferreds generally don't have a fixed maturity, although they often contain a call feature that allows the issuer to redeem them at par or a slight premium after five or 10 years. Unlike stocks, though, they don't have a stake in residual profits; therefore, preferred shareholders don't participate in the appreciation potential of other equity securities.

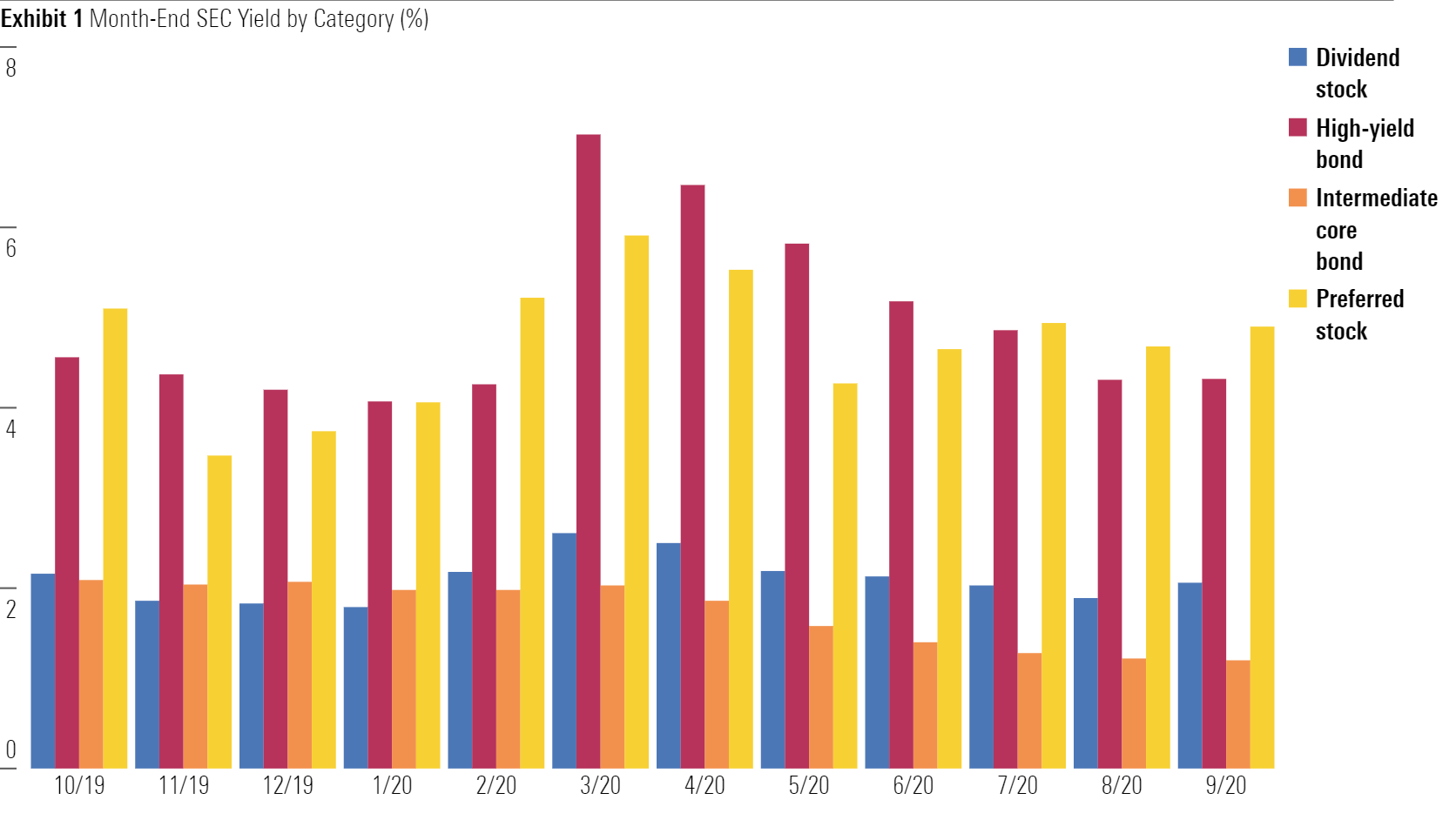

As mentioned above, yield is a key advantage for preferreds. SEC yields for preferred-stock funds averaged 4.9% as of Sept. 30, 2020, compared with 2.1% for dividend-stock funds, 4.3% for high-yield bond funds, and 1.2% for intermediate-core bond funds. Historically, preferred-stock yields are generally lower than those on high-yield credits. For the past few months, though, yields on preferred-stock funds have actually edged ahead of those on high-yield bond funds.

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of Sept. 30, 2020. Category averages include mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. Dividend stock average is based on U.S.-focused funds that include "dividend" in their names.

Preferred stocks also enjoy favorable tax treatment. Under Qualified Dividend Income tax rules, most preferred dividends are taxed at lower rates, typically either 15% or 20%. (Note: The QDI tax rate doesn’t apply to certain types of preferreds, such as hybrid preferred securities, which pay interest instead of dividends.) The QDI tax rate is well below the ordinary income tax rates that apply to most fixed-income securities. On an after-tax basis, therefore, the yield advantage of preferreds is even more compelling.

But Wait, Not So Fast Despite these advantages, there are a few reasons to be cautious.

Credit risk ranks near the top of the list. As mentioned above, preferred stockholders have to stand in line behind bondholders in the event of a corporate bankruptcy or other cash flow issue. Because preferred-stock dividends aren’t considered debt obligations, issuers also have the option of deferring payment. (Because preferred stock has priority over common stock, the issuer has to catch up on any missed dividends to preferred-stock shareholders before paying common-stock dividends.) Missed payments on preferred stock aren’t technically considered defaults, but they have the same effect on investors trying to generate income from their portfolios. Previous studies[1] have found that about 6% of preferred-stock issuers defer or cancel dividend payments over a 10-year period.

In 2020, several preferred stock issuers have either deferred or canceled their dividend payments. In June 2020, for example, Chesapeake Energy CHKAQ declared voluntary bankruptcy. As a result, the company hasn’t paid any dividends on its preferred shares since early in the first quarter. Similarly, golf course operator Drive Shack DS announced in May that it would be suspending dividends on its preferred stock as part of a broader effort to reduce expenses and restructure its financial obligations during the coronavirus pandemic.

Investors can obviously mitigate much of this stock-specific risk by getting preferred-stock exposure through a diversified mutual fund or exchange-traded fund. Even so, most funds tend to be fairly concentrated by sector, as financial services, real estate, and utilities firms account for the majority of preferred-stock issuance.

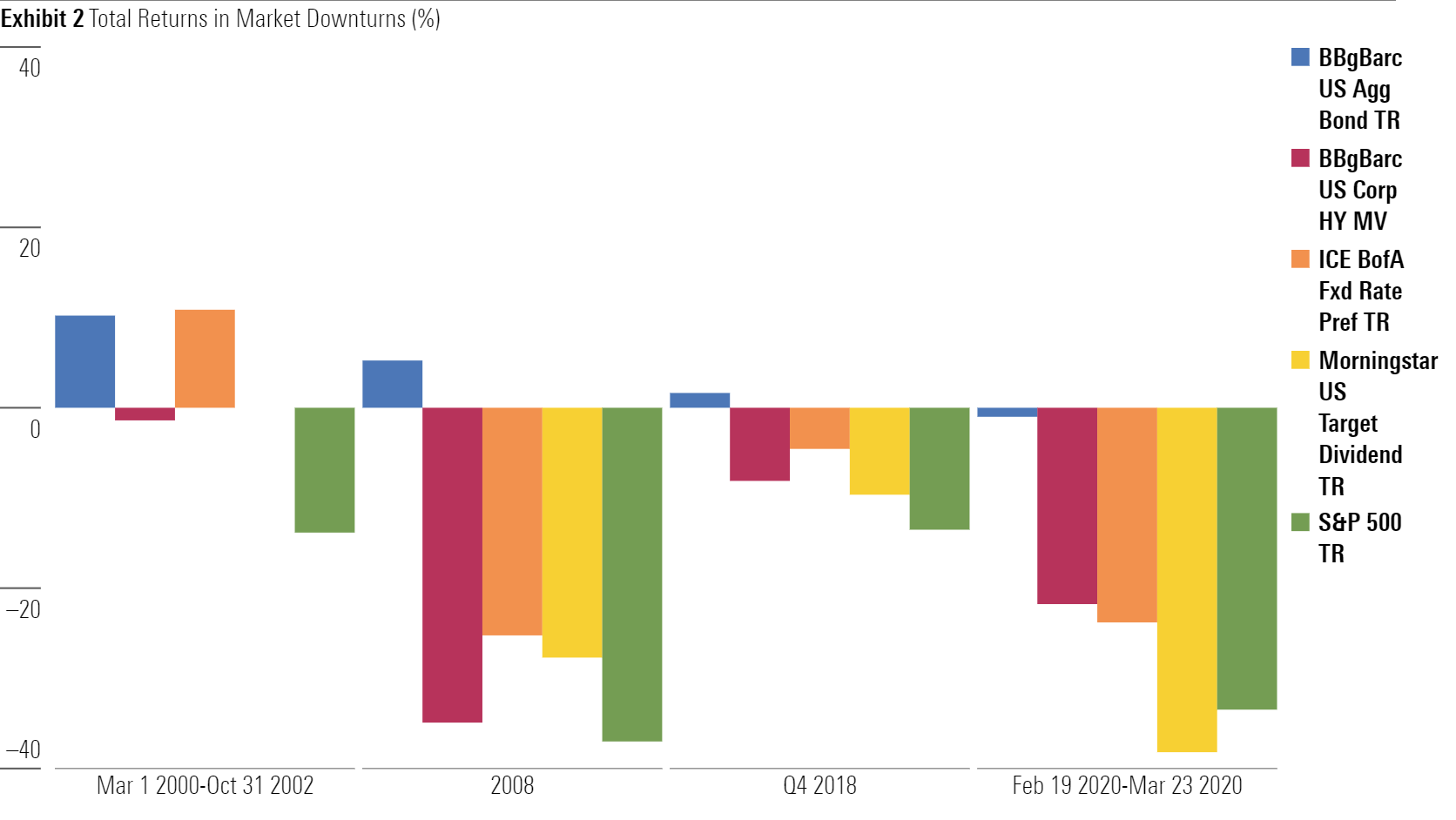

Preferred stocks’ performance in market downturns is a sobering reminder that they come with much higher risk profiles than most income-generating securities. With the exception of the technology correction in the early 2000s, when they held up relatively well, preferred stocks have typically suffered double-digit losses during market drops. In 2008, for example, the ICE BofA Fixed Rate Preferred Total Return Index dropped more than 25%. When the novel coronavirus roiled the market in early 2020, preferred stocks lost about 23%, on average.

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of Sept. 30, 2020. Returns for periods over one year are annualized.

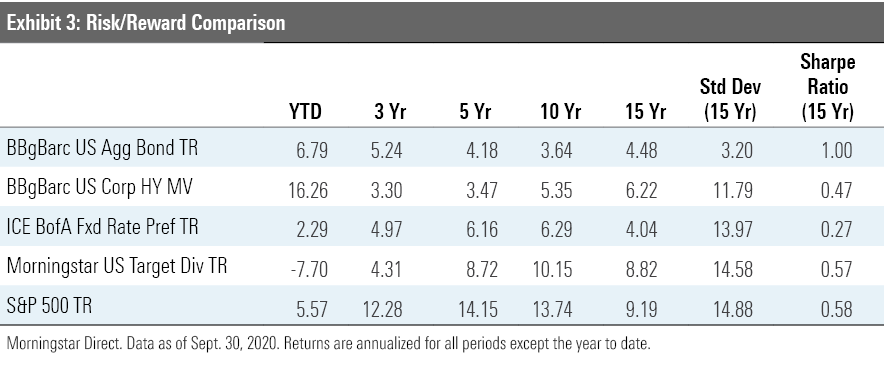

Thanks in part to their poor performance during market drawdowns, preferred stocks have generally failed to generate high enough returns to offset their risks. Over the past 15 years, preferred stocks have shown about 94% of the volatility of stocks while generating lower returns than both investment-grade and high-yield bonds. As a result, Sharpe ratios for preferred stocks have lagged those of most other income-generating asset classes over the past 15 years.

Preferred stocks won’t look quite as bad over every trailing period. The past 15 years have been unusually favorable for traditional fixed-income securities because steadily declining interest rates have led to higher-than-usual price appreciation. Now that yields have dropped so low, there’s less room for future price gains. In an environment when investment-grade bonds are likely to generate significantly lower returns, preferred stocks could look better in comparison.

Conclusion Still, it should be clear at this point that loading up on preferred stocks as a bond substitute would be a bad idea. Not only do they have much higher risk profiles than most traditional bonds, but they actually have fairly low correlations with investment-grade bond indexes. Like high-yield bonds, preferred stocks have a higher correlation with equity-market indexes than most areas of the bond market. In terms of portfolio construction, they're better viewed as a higher-yielding alternative to stocks rather than bond substitutes.

Overall, investors should regard preferred stocks with a healthy dose of skepticism. Before getting swept away by preferred stock yields, make sure you’re comfortable with their higher risk profile.

[1] Carty, L.V. 1995. "Moody's Preferred Stock Ratings and Dividend Impairment." J. Fixed Income, Vol. 5, No. 3, P. 95.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)