The Case for (and Against) Flexible Global Allocations

A flexible approach to international allocation sounds good in theory, but it doesn't always pay off in practice.

With attendees participating via live stream or optional Oculus devices, Morningstar's recent Investment Conference was about as modern as conferences get. But in the international panel, which featured Ariel Investments' Rupal Bhansali, Artisan Partners' Rezo Kanovich, and Capital Group's Rob Lovelace, a decidedly retro idea came up. When asked how much of their portfolios investors should allocate to non-U.S. stocks, the three panelists all endorsed a go-anywhere approach. Instead of setting target weightings by country or region, they argued, investors should let their global allocations drift depending on where they can find the best opportunities.

Not coincidentally, all three panelists manage funds in exactly that spirit. In this article, I’ll go through the pros and cons of adopting this style.

A Little History Back in the day, the fund world was chock-full of actively managed vehicles with more flexible investment styles. But over the past three decades or so, the landscape has shifted in favor of more narrowly defined funds that slot neatly into asset-allocation models. Many of these funds are passively managed offerings that invest in line with market benchmarks.

Even with actively managed funds, investors and asset management firms generally draw a line between U.S. and non-U.S. offerings. To wit: Foreign large-blend funds, which typically don’t have significant stakes in domestic stocks, have close to 3 times as many assets as large-cap world-stock funds, which have global mandates.

Global allocation funds—which invest in both equities and fixed-income securities around the world—have also fallen out of fashion. After peaking at $348.7 billion in assets in 2014, they now claim just $300.6 billion in assets, compared with $1.1 trillion for domestic allocation funds (not including target-date funds).

Why Go-Anywhere Makes Sense (in Theory) Flexibility may not be in vogue, but should it be more widely adopted? There are a few arguments in favor of this approach.

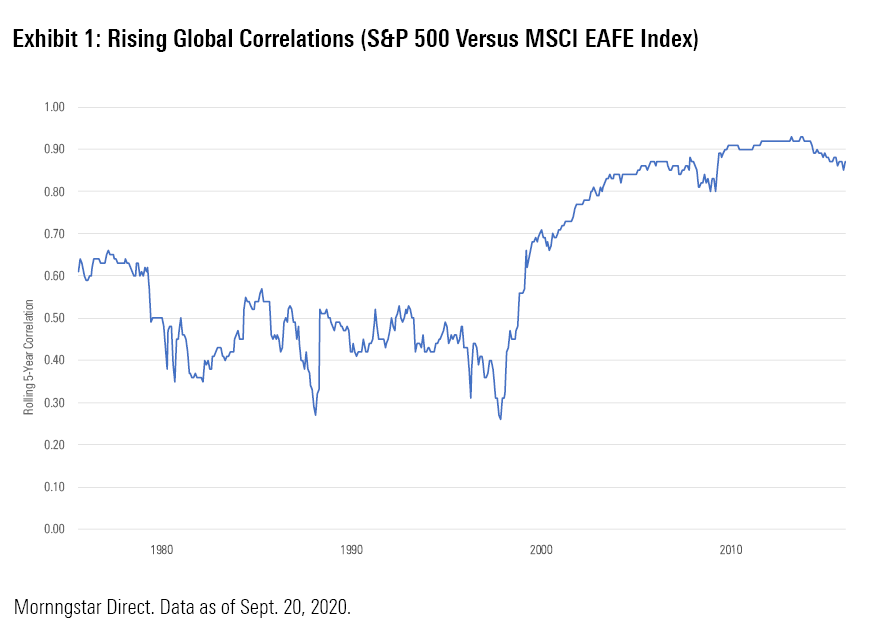

First, correlations between global markets have been rising over the past few decades. As shown in Exhibit 1, correlations between the S&P 500 and the MSCI EAFE Index have climbed to 0.88 for the trailing five-year period ended Sept. 30, 2020, up from as low as 0.27 in the mid-1980s. That means the benefits of global diversification aren’t as compelling as they used to be. Now that global markets move in the same direction more often than not, adding foreign stocks may not significantly improve risk-adjusted returns.

Second, most larger companies do business globally, which is breaking down geographic barriers. Our equity database includes information about each company's underlying revenue by region, which companies report in their regulatory filings. We can roll this up to the portfolio level to get a better view of how much global exposure lies under the surface even for "domestic" market indexes. For example, the companies included in the Russell 1000 Index generate about 40% of their revenue from outside the United States. With revenue lines blurring, there's less reason to divide up portfolios based on traditional geographic lines.

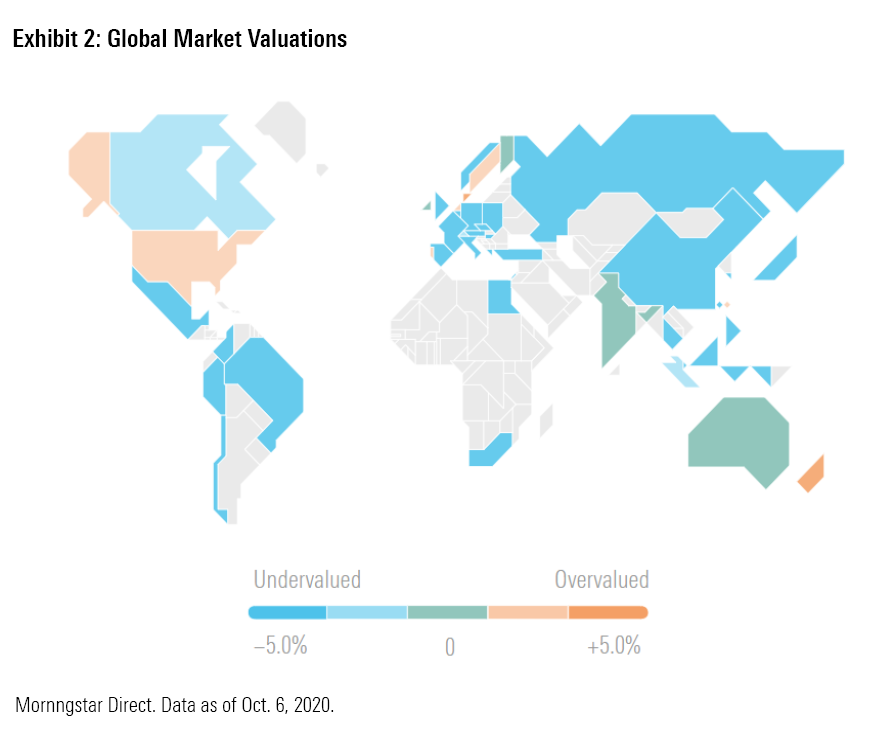

Third, valuations in the U.S. market are relatively steep. The CAPE or Shiller P/E ratio, which is based on average inflation-adjusted earnings over the past 10 years, currently stands at about 31—not an all-time high, but well above long-term averages. Morningstar's bottom-up equity research also suggests the U.S. market may be a bit overvalued. As of Sept. 30, the average U.S.-based company in our coverage universe was trading at a 3% premium to estimated fair value, which is based on our analysts’ models of projected future cash flows. As shown in Exhibit 2, valuations in other global markets look more attractive, which is another point in favor of a more flexible approach to international allocation.

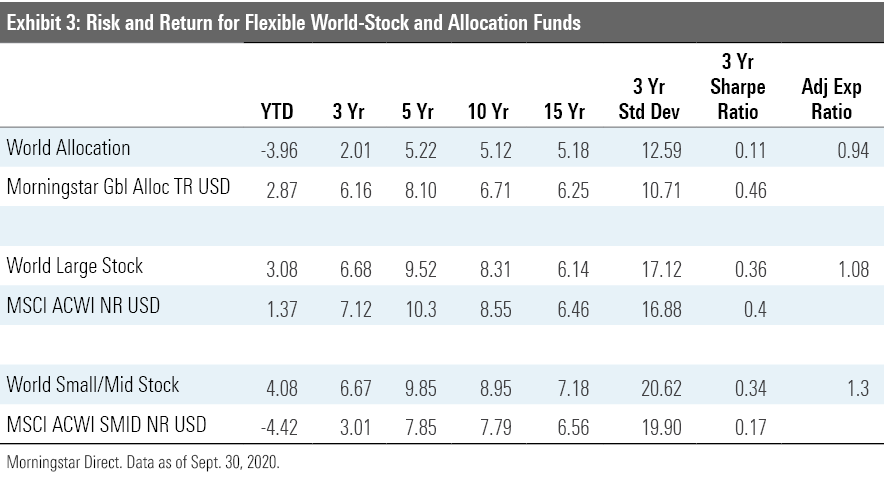

The Proof Is in the Pudding The theory sounds pretty good. But in practice, funds that take a flexible approach to geographic allocation haven't necessarily fared any better than average. As we reported in our most recent Active/Passive Barometer report, less than a third of all actively managed world-stock funds outperformed their passive rivals over the trailing 15-year period ended June 30, 2020. To home in on the most flexible funds, I also looked at actively managed funds with regional allocations that were significantly different from global market benchmarks. On average, they trailed passively managed indexes over most trailing time periods.

Small- and mid-cap funds fared the best of the three categories. Because smaller-cap stocks are less widely followed, there’s more of an opportunity for flexible, opportunistic managers to add value. The subset of flexible funds in the world small/mid stock Morningstar Category came out ahead of the comparable market benchmark by about 60 basis points per year over the trailing 15-year period, although those numbers would look worse without the benefit of survivorship bias.

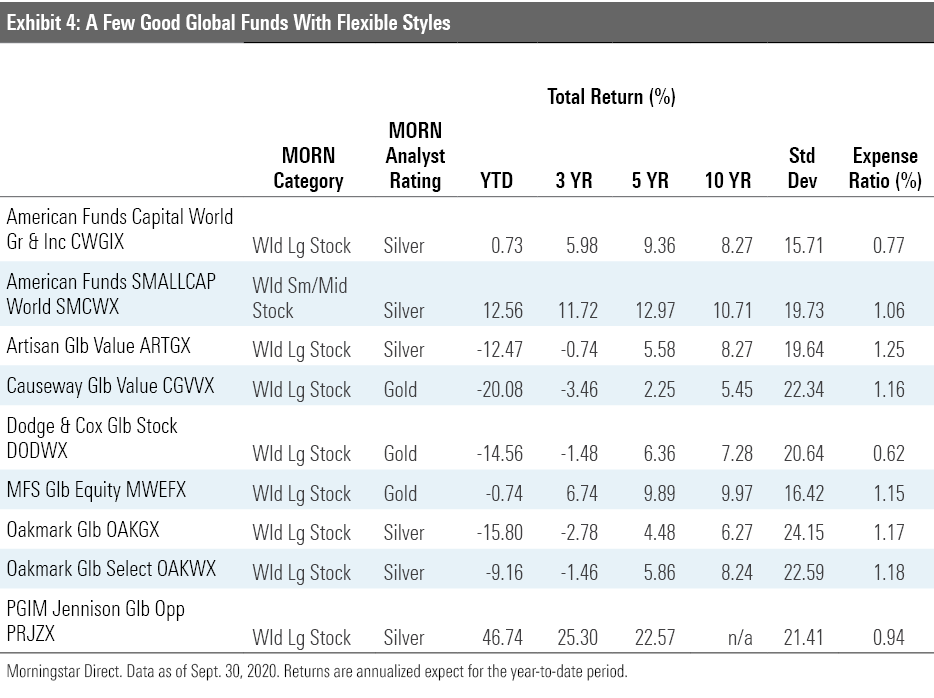

While actively managed global funds as a group haven’t consistently outpaced their passively managed peers, there are a few standouts. Exhibit 4 highlights world-stock funds that take a more flexible approach to country and regional allocation and have earned Morningstar Analyst Ratings of Gold or Silver.

Conclusion A more flexible approach to international allocation isn't for everyone. Even with rising correlations between global markets, there's still some benefit to be had from international diversification. As long as the correlation coefficient between U.S. and non-U.S. markets remains below 1.0, adding international exposure should still improve risk-adjusted returns over time. Some investors might also want to maintain a specific international target to make sure their portfolios have a certain level of exposure to non-U.S. currencies. That's especially true now that the U.S. dollar has shown some signs of weakening after generally trending up since late 2011.

If you decide to invest in a fund with a more flexible approach, it’s also important to make sure you’re comfortable with the underlying allocations. Country and regional weightings vary widely, with some funds holding significant weightings in U.S.-based stocks. As mentioned above, these holdings may have underlying revenue exposure from overseas, but don’t offer direct exposure to foreign equity markets and currencies.

At the end of the day, the strongest argument in favor of a more flexible approach is that it allows investors to maximize the global opportunity set. The evidence that this approach can pay off in practice is mixed, though.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/F2S5UYTO5JG4FOO3S7LPAAIGO4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7TFN7NDQ5ZHI3PCISRCSC75K5U.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/QFQHXAHS7NCLFPIIBXZZZWXMXA.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)