Sustainability Matters: New SEC Rule Weakens Influence of Main Street Investors

Shareholder proposals play a central role in corporate governance.

SEC chair Jay Clayton, he who helps make a foursome for the president's golf outings and whom the president wants to appoint federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York, is fond of saying he's all about protecting the interests of "Main Street investors."

In fact, a group called "The Main Street Investors Coalition" emerged in 2018 to support Clayton's efforts to make changes to the rules by which investors could propose shareholder resolutions at company annual general meetings and to limit the ability of proxy advisors to give unvarnished voting advice to shareholders. What seemed odd was that the SEC's proposals made it harder for everyday investors to participate in corporate governance.

Alas, "The Main Street Investors Coalition" turned out to be a totally fake grassroots entity (referred to by those in the know as an "Astroturf" group). It was apparently funded by the National Association of Manufacturers. Once exposed, it disappeared from view, but not before Clayton referred to what appeared to be fake public comment letters he said came from "Main Street investors" supporting his views in testimony before Congress earlier this year.

So that explains it. By “protecting Main Street investors,” what Clayton really means is that he wants to protect corporations from small investors proposing too many bothersome resolutions. Why? The stated claim is to “modernize” the rules in order to make it more costly for Main Street investors to offer resolutions because responding to their resolutions costs corporations money, which leaves less profit for all the other small investors. Implicit in that argument is the assumption that the entire process is without any value to shareholders.

Clayton and his two Republican colleagues on the SEC voted Wednesday to finalize a rule that would vastly increase the size of the stake in a company that a "Main Street investor" needs to hold in order to propose a shareholder question at a company's annual general meeting and significantly increase the amount of overall shareholder support a resolution needs in order to qualify for resubmission. The two Democratic appointees on the SEC, Allison Herren Lee and Caroline Crenshaw, opposed the rule.

Currently, an investor must own at least $2,000 worth of stock for one year to be able to propose a resolution. Under the new rule, an investor must own at least $25,000 worth of stock for one year to be able to propose a resolution, or $15,000 for two years, or $2,000 for three or more years. Smaller shareholders can no longer band together to meet these submission thresholds.

Currently, a proposal needs to garner 3% of votes to be eligible for resubmission, 6% on a second vote to be eligible for resubmission, and then 10% thereafter. The new rule raises those thresholds to 5%, 15%, and 25%.

The stated rationale for the changes is that resolutions appearing on company proxy ballots year after year are burdensome and unjustified. But, as we argued in Morningstar's comment letter to the SEC, raising the bar for shareholders who wish to file proposals is a step in the wrong direction. Shareholder resolutions make financial markets better, not worse, for Main Street investors.

Shareholder resolutions help investors seeking long-term value. Shareholder resolutions have been a key part of how shareholder democracy works in the United States since the 1950s. They provide a way to surface information and initiate discussion about emerging risks in a well-functioning market. These risks have always included those related to corporate governance, but importantly and more recently, they now include environmental and social risks.

Shareholder resolutions send important signals to corporate management about investor concerns and often lead to notable changes. Shareholder concerns surfaced in the resolution process have led to new practices being widely adopted across markets, including, for example, electing directors by majority vote and giving shareholders the opportunity to vote on executive compensation practices.

Shareholder resolutions have led to enhanced disclosure of sustainability and climate risks. The shareholder-resolution process has sent a crucial signal to companies that they need more information about these risks and how companies plan on managing them.

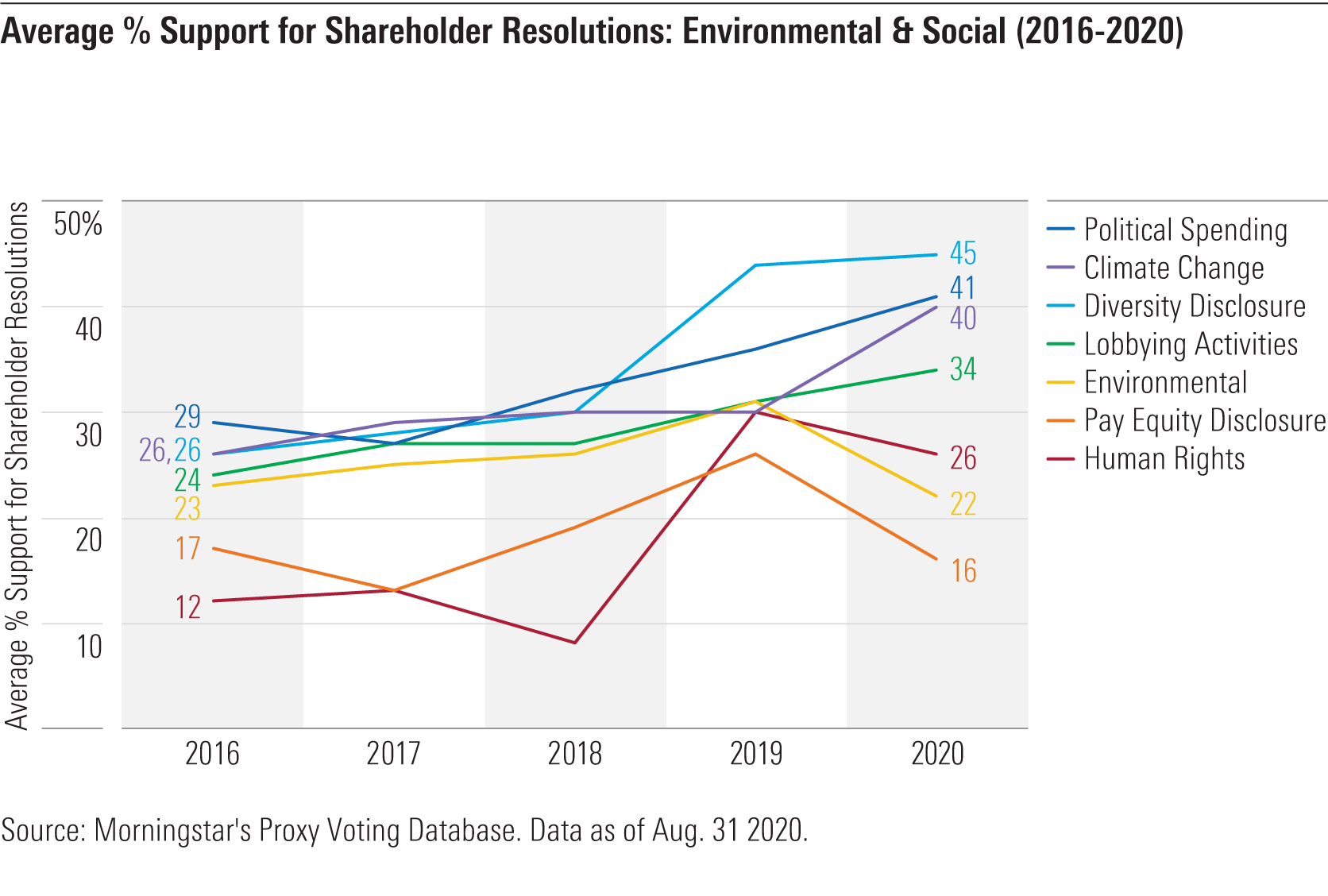

Average support for shareholder resolutions on environmental and social issues has been steadily increasing, with average support doubling between 2004 and 2018. Exhibit 1 shows levels of support over the past five years. It’s been growing in six of the seven topic areas shown. Interestingly, average support for pay equity disclosure resolutions declined in 2020. That’s because several of these resolutions asked for racial pay equity disclosures, a newer topic prompted by racial equity concerns that have soared to the top of the agenda this summer. As shareholders become more familiar with the topic and set their expectations, support for racial pay equity disclosure resolutions may increase in subsequent years, but, with the new rules, such resolutions must now generate higher levels of support to be refiled.

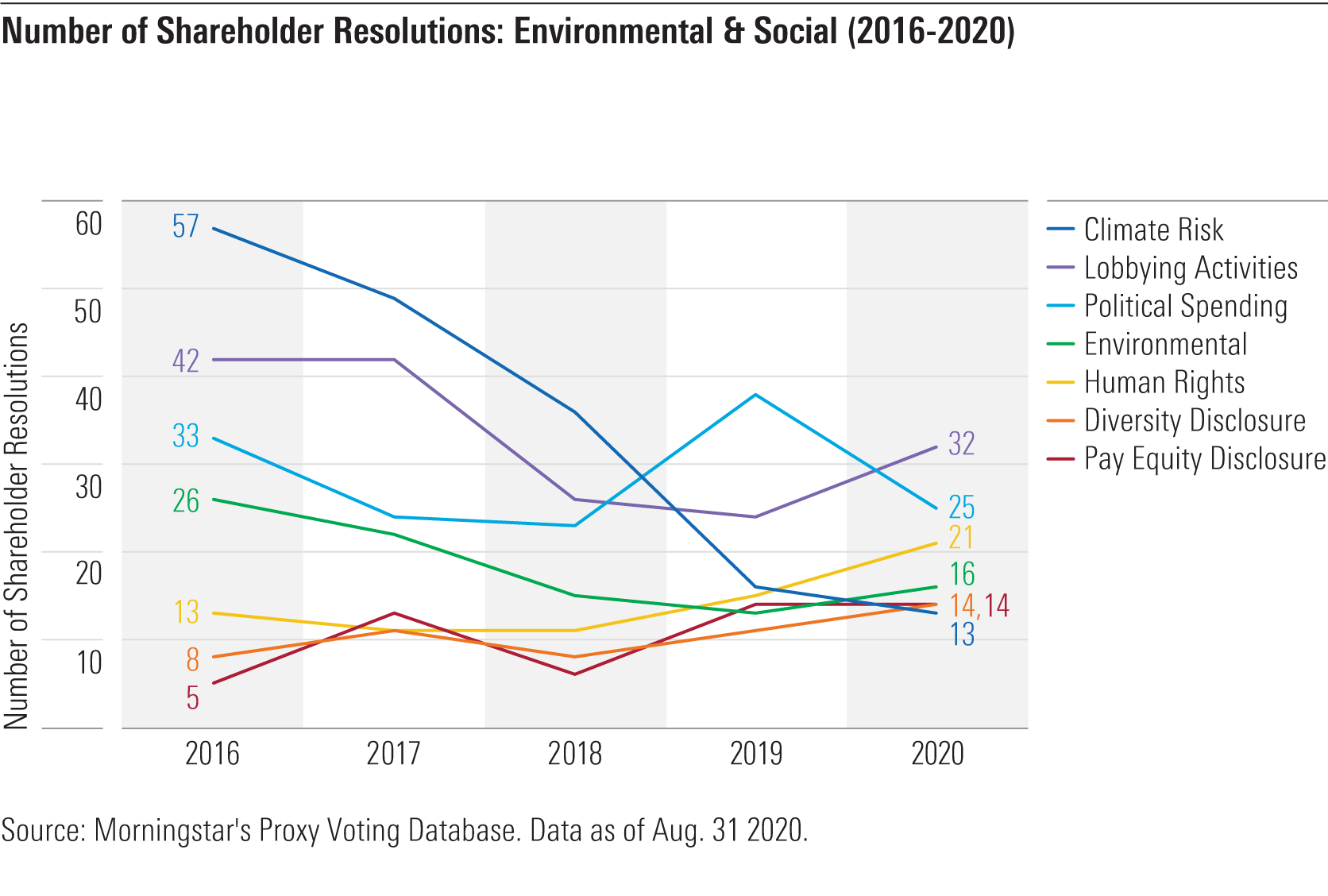

Shareholder resolutions prompt direct engagement with companies. Proposals often spur shareholders and management to meet for a full discussion of the topic. This, in turn, leads to proposals being withdrawn and corporate managements agreeing to address issues, something that happens frequently every year. As Exhibit 2 shows, fewer environmental and social shareholder resolutions have come to a vote in recent years in four of the topic areas, including climate risk. It is not uncommon today for as many proposals to be withdrawn before the vote as there are proposals that make it to a vote.

Importantly, shareholder resolutions proposed by smaller investors prompt large institutional investors, including asset managers and asset owners, to engage with corporate managements on high-profile issues. We see no reason to diminish this dynamic, which produces significant impact.

The benefits of shareholder resolutions greatly outweigh the costs. The SEC's version of the problem may lead one to think that the shareholder resolution process is out of control, inundated by small publicity-seeking activists pushing their pet issues. Yet the number of resolutions voted on each year has remained fairly constant over the past two decades, and, as Exhibit 2 shows, fewer environmental and social resolutions have been voted in recent years.

But as Exhibit 1 shows, average shareholder support for environmental and social resolutions, in particular, continues to grow. This, in itself, is a benefit of the process. It means investors are signaling real concerns to companies that need to be addressed. If resolutions were just nuisances, then presumably they wouldn’t be garnering much support and might rightly be called out as costly. By the SEC’s own estimate, resolutions “cost” companies in the Russell 3000 $70 million per year. That averages out to just $23,000 per firm. According to commissioner Lee, only about 13% of companies, on average, received a shareholder proposal between 2004 and 2017. The benefits of even a single successful resolution or engagement to a company that addresses a significant shareholder concern could dwarf not only the SEC’s per-firm cost estimate but also the overall annual cost estimate.

In sum, shareholder resolutions and the proxy process make financial markets better for ordinary investors. While the process will persevere under its new limits, there was no good reason for this rule, other than a Trump administration regulator taking action on behalf of certain D.C.-based business trade organizations that want to stifle the voice of investors who have indeed been more concerned in recent years about how public companies address ESG risks, especially those related to climate change.

Jon Hale (jon.hale@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1995. He is Morningstar’s director of ESG research for the Americas and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. While Morningstar typically agrees with the views Jon expresses on ESG matters, they represent his own views.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/42c1ea94-d6c0-4bf1-a767-7f56026627df.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DJVWK4TWZBCJZJOMX425TEY2KQ.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/Q27ZB7KFPZBMHFKY6IURRWJQHM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)