A Closer Look at the Future of Clean Shares

As new share classes evolve, we untangle their meaning.

Clean shares.

The term has a nice ring to it. After all, who wants to invest in dirty shares? Over the past year or so, we at Morningstar have been working to wrap our arms around this new term, identifying emerging share classes and helping investors understand what these new share classes might mean for them.

Our first observation: We do not love the name. “Clean shares” jumped the pond from the United Kingdom after new rules called the Retail Distribution Review went live in 2013. The term implies that anything called “clean” is the best choice for an investor, and that is not necessarily the case. Given the different flavors of new share classes, we believe more descriptive names and categories would help mutual fund investors understand the answer to a few key questions: Who are they paying directly and who is being paid indirectly for services? What conflicts of interest might any indirect payments create?

The Dash to Offer New Share Classes At the beginning of 2017, in response to the U.S. Department of Labor's fiduciary rule, mutual funds began to consider offering a new share class. The idea was a direct response to key details in the best-interest contract exemption part of the fiduciary rule. The rule's warranty section required firms to eliminate incentives for advisors to recommend one similar product over another based on compensation the product pays the firm.

Mutual funds created “clean” shares to reduce these conflicts of interest by eliminating, or at least leveling, payments from asset managers to the intermediaries that sell mutual funds. Intermediaries would then ensure their advisors’ compensations did not depend on the fund they recommended, reducing conflicts of interest.

On Jan. 11, 2017, the SEC cleared the way for these new share classes but left some key questions unanswered. In a no-action letter to a fund complex, the SEC clarified that mutual funds can offer clean shares under an arcane part of the 1940 Investment Company Act, known as Section 22(d). These new share classes would be different from traditional share classes because they would change the way intermediaries collect commissions and other fees for selling funds. Instead of investors paying fees to a mutual fund, which in turn paid them back to intermediaries and ultimately financial advisors, the clean share would allow intermediaries to charge a fee to sell a fund.

However, the SEC did not provide much information beyond writing that clean shares could not include distribution fees (also known as 12b-1 fees) and load-sharing (when a fund collects a load, usually up front, and shares it as a commission with the broker/dealer who sells the fund). Under the no-action letter, funds were free to include other kinds of payments to intermediaries that would sell their clean shares.

This was just the beginning of a discussion that asset managers, broker/dealers, financial advisors, and others in the industry are still having about how to define clean shares. In the summer of 2017, the Department of Labor issued two requests for information asking whether endorsing clean shares, and writing regulation to encourage them, would be helpful.

We—and many others—told the government that clean shares represented a promising innovation, but we noted that writing regulations to promote the nascent idea would be challenging. The government would be trying to build regulations around a product without a clear definition, and at some firms, clean shares could still have elements that might lead to conflicted advice. Even though some asset managers have already created new, innovative share classes that meet principles of the rule, endorsing a particular version of clean shares could stifle innovation.

In November, the Department of Labor delayed the fiduciary rule’s implementation, causing the industry to press the pause button on clean shares. However, there continues to be interest in improving fund distribution, and new versions of clean shares will be a big part of how the industry does so. In addition, the hugely important defined-contribution retirement plan market is increasingly using types of clean shares.

From 'Clean' to 'Service-Fee Arrangement' There still is no common definition of "clean." There is universal agreement that clean shares will not have loads or 12b-1 fees, which are both fees used to pay for a mutual fund's distribution costs. But there continues to be disagreement about whether clean shares should include subtransfer agency fees for recordkeeping (often called sub-TA fees) and other kinds of revenue sharing where a mutual fund's advisor pays an intermediary. A big part of the definition depends on what we expect clean shares to do and what kinds of conflicts they are designed to mitigate.

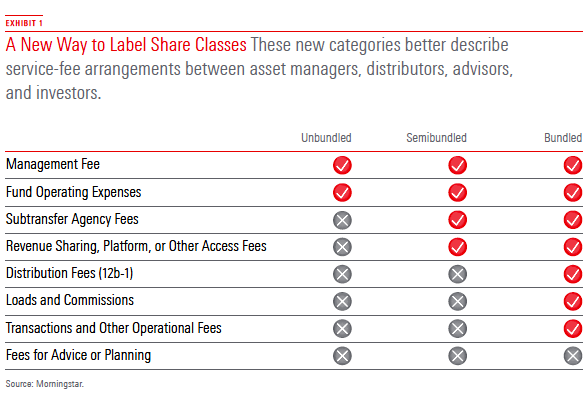

To help investors and the industry untangle what these new share classes mean, we plan to label emerging share classes a little differently. Although “clean” may stick in the lexicon (particularly given that the SEC used the term in its no-action letter), the heart of our idea is to describe the service-fee arrangement and shed light on what an investor pays for, whether it’s directly (say, by writing a check to an advisor) or indirectly (via a fund’s expense ratio). We think that most share classes fit into three broad buckets: unbundled, semibundled, and bundled ( EXHIBIT 1 ):

Unbundled

Investor simply pays for investment management and fund operating expenses, and the fund and its advisor do not pay third parties who sell their funds to the public.

Semibundled No traditional distribution fees (or 12b-1 fees) or load-sharing but can have revenue sharing or sub-TA fees.

Bundled Traditional share classes, where the investor pays a load and a 12b-1 to the mutual fund, which in turn pays the intermediary.

Users of Morningstar Direct and Advisor Workstation will begin seeing these new labels soon for all U.S. funds at the share class level under "Clean Share—Service Fee Arrangement."

What Do They Mean for Investors? The unbundled and semibundled categories are not necessarily the best for every investor. Rather, each of these service arrangements can be appropriate for different kinds of investors. In fact, the unbundled share class could end up costing investors the most. Each type of service arrangement also raises different questions investors should ask their advisor. And whatever the type of service-fee arrangement, there is one question clients should always ask their advisors: Are they acting as a fiduciary, as someone who puts their clients' interests ahead of their own?

Unbundled share classes reduce conflicts, but investors still need to ask if they are paying a reasonable amount for advice and for the services that their intermediary charges them directly. For example, investors in unbundled share classes may be in a wrap account, where they pay a percentage fee to cover all administrative and management expenses and do not pay a commission when they rebalance. These arrangements may not be appropriate for every investor, and often cost 1% or more of assets under management each year. However, investors in 401(k) plans will almost always be better off with unbundled share classes, all else equal, as they represent the cheapest way for them to invest.

Semibundled share classes could create some potential conflicts of interests that investors need to ask about. For example, these arrangements can be the deciding factor for a fund to get onto an intermediary’s platform. Further, if funds vary in how much revenue sharing they pay to intermediaries, it could create incentives for advisors to push one fund over another. Investors should ask if advisors or their firms have taken steps to mitigate these potential conflicts of interest. For example, some firms say that all funds on their platform pay the same amount for sub-TA and revenue sharing, reducing conflicts of interest. Investors should also ask about which funds are not on the platform— and why. Many retail investors will increasingly be offered semibundled share classes instead of bundled share classes. If firms mitigate any conflicts these can create, they can work well for many retail investors.

Bundled share classes are purely transactional, which can work well for sophisticated investors who have done their homework and wish to pay up-front commissions. Advice associated with these share classes may ultimately cost less, particularly with rights of accumulation. Investors should ask themselves how much they understand about their advisor’s compensation and whether they have scrutinized recommendations. Selling funds with loads has been a practice in long-term structural decline, but that arrangement can be best for some investors.

Promising Innovation While the momentum toward clean and unbundled share classes slowed a bit this year, we expect it to rebuild, and we welcome that trend. That said, these promising innovations are not standardized, and one version won't necessarily be best for all investors. Our system of evaluating and classifying each share class according to its service-fee arrangement will help investors and advisors make best-interest assessments.

Janet Yang, global data director, core managed investments, with Morningstar, and Lia Mitchell, a data content researcher with Morningstar, contributed to this article.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2018 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)