Slow and Steady Wins the Race--in the Land of Make-Believe

Long-term outperformance is a rocky road requiring patience and resolve.

Howard Marks is the co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, a well-known bond and alternatives investing specialist. Marks is a legend in asset-management circles, having amassed an outstanding record, and his memos are considered de rigueur within the corridors of Wall Street and well beyond (Warren Buffett is one of Marks' most devoted readers). One such memo, "The Route to Performance," was published in 1990:

"As an alternative, I would like to cite the approach of a major Midwest pension plan whose director I spoke with last month. The return on the plan's equities over the past 14 years, under the direction of this man and his predecessors, has been way ahead of the S&P 500. He shared with me what he considered the key: "We have never had a year below the 47th percentile over that period or, until 1990, above the 27th percentile. As a result, we are in the fourth percentile for the 14-year period as a whole.' "

But among active U.S. equity funds, the pension manager Marks describes above might as well be a unicorn or mermaid. Indeed, such funds perform with nowhere near the kind of unerring consistency of Marks' pension manager. Thus, while well-intentioned, the quest for "slow and steady" is largely misguided. Instead, investors are well advised to assume that the most successful funds will be erratic, driving them nuts at times, with all the associated nerves and nausea. (Most investors aren't cut out for this and therefore should index.) In the remainder of this piece, we illustrate this by examining patterns in U.S. equity fund performance and offering some thoughts on what an active-fund investor is to do when "slow and steady" is a mirage.

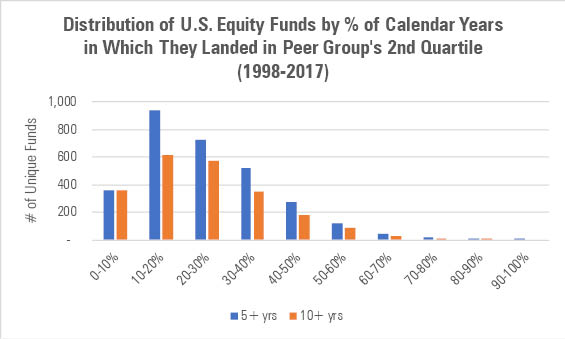

Puff, the Magic Portfolio Manager? We examined the calendar-year net returns of more than 4,800 unique U.S. stock funds for the two-decade period 1998 through 2017, including dead funds. We category-peer-ranked the funds each calendar year based on their net returns and then tallied up the number of second-quartile finishes each fund achieved during the 20-year period.

Of the 4,807 funds we examined, 3,343 lived through at least five calendar years. Of those 3,343, a grand total of 15 funds--or 0.5%--managed to land in the second quartile of their peer group in at least three of every four calendar years. But when you consider that seven of those 15 funds were index funds, the pool of slow-and-steady funds shrinks to almost nothing.

Speaking of nothing, of the 2,158 active U.S. stock funds that lived through at least 10 calendar years, not a single fund landed in the second-quartile of its peer group in at least three quarters of the years. The most successful active stock fund by this measure,

The chart below illustrates how uncommon it was for equity funds to finish in their peer group's second quartile with any kind of regularity. On average, U.S. stock funds landed in the second quartile only about 24% of the time, or in roughly one of every four calendar years, irrespective of whether they lived through at least five or 10 calendar years.

Source: Morningstar.

There's No Puff? The slow-and-steady equity-fund manager is a fuzzy myth; thus, investors hunting for such funds are largely wasting their time.

Instead, investors would be well advised to ask themselves whether they have the stomach and nerve to remain with active funds that are anything but slow-and-steady. Do they have what it takes to identify and stick with long-term successful funds that wheeze and lurch, confound, and frustrate over the short term? Most don't and therefore should index.

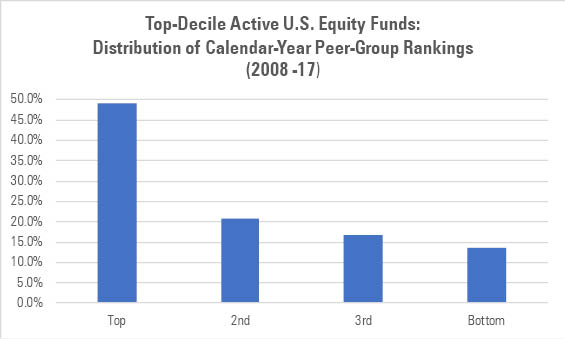

But for those who do (or who have not shaken themselves of that delusion), here is what they'd see when they peer through the other end of the looking glass: Top-performing funds routinely underperform, sometimes by a lot.

Source: Morningstar.

The above funds--which ranked in the top 10% of their peer groups over the 10-year period ended Dec. 31, 2017--obviously performed well. But the chart also makes it clear that they were no strangers to the bottom half or even the lowest quartile of their peer groups: All told, these 174 standout active U.S. stock funds lagged or cellar-dwelled in about one of every three calendar years, with 109 of these funds spending at least one calendar year in its peer group's bottom quartile.

Conclusion Rather than chase a narrative--that of the slow-but-steady mutual fund that romps over the long haul--hunker down. Grapple with the realities of investing in active funds, where underperformance is a feature, not a bug. This demands patience, resolve, and not a little contrarianism, as mean-reversion is a pervasive force.

For most investors, that process will prove to be too much--they lack the time, the constitution, or both--and for them a low-cost passive fund is a prudent choice. But for those who have the stomach and steel, they're likely to be best-served focusing on managers who know the true meaning of slow but steady, as evidenced by a strong commitment to the investment process, a supportive, shareholder-friendly parent, and competitive fees that give the strategy a fighting change of succeeding over the long haul.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)