Capital Group, Part II: Knowing Its Limits

This longtime manager of massive funds needs to clarify its own capacity constraints.

A prior Fund Spy argued that American Funds parent Capital Group's long-term investment results, fixed-income improvements, and industry leadership ensure its relevancy even as cheap passive options and regulatory changes pressure active managers to cut costs and improve performance.

This Fund Spy focuses on capacity. Capital Group’s divide-and-conquer approach to asset management has long enabled it to run massive funds. However, it’s time for the firm to better specify the funds’ capacity and explain its reasoning for those limits.

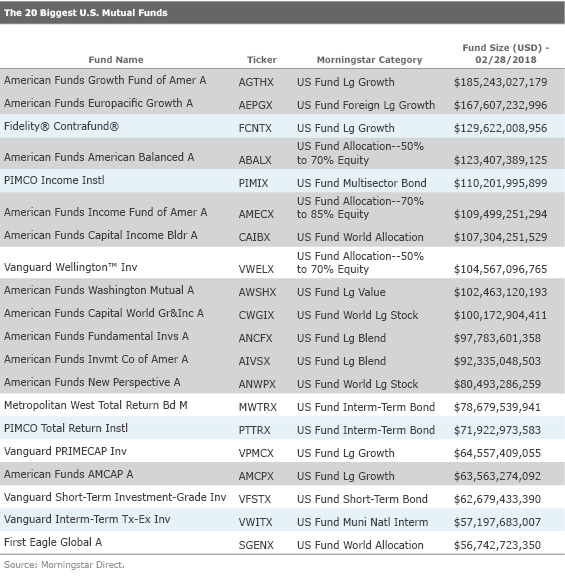

Big and Good for a Long Time American Funds' offerings predominate in any list of the industry's biggest. As of February 2018, 11 were among the top 20 actively managed equity, balanced, or fixed-income funds in the United States and eight of the top 10 stock funds were American funds.

Managing gargantuan asset bases is not new to Capital Group. In 1969, for example,

A Better Mousetrap One can argue that Capital Group has built a better mousetrap for managing huge sums of money. Initially developed in 1958 to manage equities, the firm's multimanager system divides each fund's asset base into independently run sleeves, including an analyst-run research portfolio. Each fund's overall portfolio is composed of many subportfolios whose holdings overlap to varying degrees because they are run by managers whose styles and risk tolerances differ.

Capital Group took that principle a step further in 1998 when it first formally separated into different investment groups. As of June 2017 (the most recent data available), the firm managed more than $1.7 trillion in discretionary assets through three equity investment divisions—Capital World Investors (CWI), Capital Research Global Investors (CRGI), and Capital International Investors—and one fixed-income division, Capital Fixed Income Investors. Each division has 25 to 30 veteran portfolio managers and 40 to 50 experienced analysts. These groups aren’t totally isolated—for instance, the bond managers work with the equity managers in running the firm’s balanced funds—but the equity divisions don’t share investment ideas with one another.

Thus, in the case of funds with asset bases split between equity divisions, the risk of their respective management and analyst teams focusing on a narrow set of opportunities is greatly reduced. Even when managers in separate groups do independently buy the same stock, each group’s investment thesis is likely to differ, to say nothing of how the interpretation and style-based application of an investment thesis can differ across managers within a group. This confers greater capacity than could be achieved otherwise.

A Resurgence in Flows and Overseas Expansion Efforts American Funds' ability to handle additional capacity has again come to the fore. Although its lineup experienced considerable outflows in the years following the 2007-09 financial crisis, that trend has started to reverse. Investors have shown renewed interest, especially following the firm's late-2016 decision to make its no-load F1 shares available on various brokerage platforms, beginning with Schwab and Fidelity. The fund family saw positive inflows in 10 of out 12 months in 2017, and took in an estimated $7.9 billion in January 2018, its biggest monthly haul since October 2007. U.S. equities was the only asset class to see outflows in January 2018, but the money channeled into international equities more than made up for that.

The resurgence in fund flows also comes as Capital Group tries to expand overseas. Since October 2015, Capital Group has been replicating funds like

Capacity Monitoring at Capital Group The potential for U.S. and non-U.S. investors to pour money into the same strategies raises the stakes for capacity monitoring. As Warren Buffett memorably put it, "huge sums invariably act as an anchor on investment performance." [2] Thus, it behooves investors and observers to consider at what point size would begin to impede Capital Group's ability to effectively manage money.

To this point, Capital Group pays heed to simple guidelines for assessing its funds’ capacity. For example, when “a particular fund’s or mandate’s assets reach 1.5% of its investment universe, this triggers a closer review to be sure we are adequately pursuing superior returns.” [3] Thus hitting that limit won’t necessarily lead Capital Group to close a fund to new investors, but it does spur analysis that could lead to that. As a proxy for each fund’s investment universe, the firm uses the aggregate market cap of its index. For instance, American Funds Growth Fund of America’s AGTHX $177.5 billion asset base at year-end 2017 accounted for less than 0.8% of the S&P 500's aggregate market cap, suggesting to the firm that a review based on size alone was far from warranted.

Comparing Growth Fund of America’s asset base to the S&P 500's aggregate market cap does provide a gauge of the fund’s size relative to large-cap U.S. equities. The fund, though, can invest up to 25% of assets overseas. It is thus somewhat misleading to compare Growth Fund of America’s asset base to the aggregate market cap of the domestic S&P 500 when its actual investment universe is bigger. After all, if the fund in theory had exhausted all the attractive options in the United States, it would still have the whole universe of non-U.S. equities to choose from for one fourth of its portfolio. In that respect, there is more potential capacity than the comparison suggests.

In another respect, there is far less capacity than the comparison suggests. Growth Fund of America’s true investment universe, while broadened by its geographical flexibility, is in practice constrained by other factors. The SEC requires greater disclosure if either equity division managing the fund’s asset base—CWI or CRGI—owns 10% or more of a company’s outstanding shares and the firm has an internal guideline that caps a fund’s individual company ownership at 8% of shares outstanding.

However one defines “capacity”, it quickly becomes apparent that Capital Group could do more to show that its 1.5% threshold accounts for these practical constraints and, furthermore, leaves the firm’s portfolio managers with enough flexibility to run their sleeves in an unfettered way. For instance, we would welcome public disclosure of findings from “stress tests” in which Capital Group evaluates a fund’s capacity and attributes under various asset-growth scenarios. We also would welcome further rationale supporting the appropriateness of the 1.5% threshold for all mandates, including those that would seem to be more capacity-constrained, like global small- and mid-cap stocks or emerging-markets equities.

Capital Group has done a responsible job of putting a scalable system in place, but it has a history of relaxing capacity limits. Internal company ownership caps have been raised over time for its biggest funds, including Growth Fund of America. The firm’s 1.5% threshold had originally been 1% and was increased when the firm realized it could manage more money. Finally, Growth Fund of America’s cap on overseas investing had been 10% at year-end 2009, when the fund’s asset base then accounted for 1.57% of the S&P 500’s aggregate market cap, and the firm then changed that cap to 25% in 2010. The timing, at the very least, raises the question of how the firm will respond if a fund’s asset base again crosses the 1.5% threshold.

Looking Forward To be sure, we've already registered some of our concerns about capacity in our ratings of certain American funds, like Growth Fund of America. Although the fund has flourished in recent years as mega-caps have outperformed, its Morningstar Analyst Rating of Bronze is lower than most of its American Funds' equity peers because its asset base constrains its ability to take big positions in mid-cap and even some large-cap stocks. At year-end 2017, for example, the fund's 94-basis-point position in the $22 billion market-cap company Concho Resources CXO accounted for roughly 7.3% of Concho's shares outstanding, which was near the fund's own internal 8% cap.

While capacity concerns might otherwise have taken a backseat when the American funds were mired in outflows in recent years, there’s more urgency now. Given the lineup’s greater accessibility and Capital Group’s clear desire to further its ambitions through orderly future growth, we think the firm has as an opportunity to set a new standard for transparency in monitoring and managing capacity. We’d encourage Capital Group to keep investors apprised of its efforts to ensure that asset size doesn’t compromise managers’ ability to add value, including outlining the conditions that would lead to proactive closure of a fund to new investors. This could only serve to increase current shareholders’ confidence in an asset manager that has long served them well. It would also help ensure that the firm’s relevance endures.

[1] Charles D. Ellis, Capital: The Story of Long-Term Investment Excellence (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2004), 19, n. 22.

[2] Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., 2016 Annual Report, 24.

[3] Capital Group, Strategy Insights December 2016, Asset Growth and Size – Equity, 6.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/08b315db-4874-427f-b3b1-f2b84a16e609.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/08b315db-4874-427f-b3b1-f2b84a16e609.jpg)