Fantastic Yields and Where to Find Them

Some funds with big yields have huge risks, but others take risks wisely.

The following article was originally published in the March issue of Morningstar FundInvestor.

I've often warned against buying and selling funds based on short-term performance. Buying based on yield might be even worse, however.

Whether you are doing it on a stock, bond, or fund basis, the highest-yielding securities in a peer group are usually the highest risk. The market is awfully efficient at finding values in yield, so if something has a big yield, watch out.

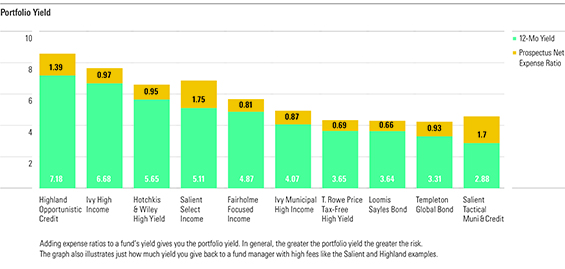

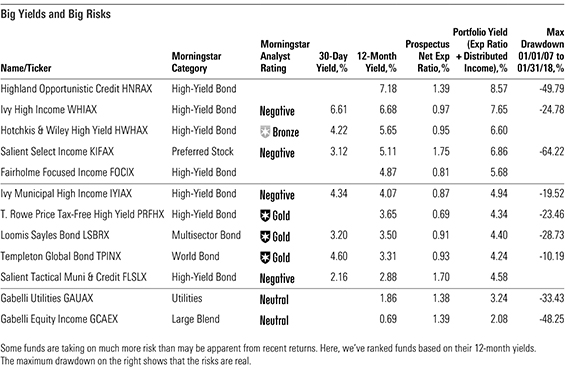

For mutual funds, we worry when we see a fund with a yield that's, say, 200 basis points or more above peers and benchmark. Of course, it varies from category to category, but big yields are a big red flag. The best way to view yield when you are looking for warning signs is to add the expense ratio back to the yield so that you have the portfolio yield. Expenses are subtracted from portfolio income before anything is paid out, so they detract from yield by their full amount. Thus, high-cost funds with big yields are often taking on even more risk than their yield might suggest, while low-cost funds might be taking less risk.

What makes the big-yielding funds particularly tricky is that they can have years of fairly steady returns that mask their underlying risks. In 2007, I wrote that Oppenheimer's muni funds, including Oppenheimer Rochester Municipals Fund RMUNX, were not all that great despite their strong 10-year returns. A number of brokers wrote in to say that was ridiculous. Then, in 2008, the funds' highly credit-sensitive and leveraged portfolios got thumped, thanks in part to exposure to a number of particularly hard-hit parts of the muni market, including tobacco-settlement and land-secured bonds.

There are a few ways to boost a fund's yield. Most of them are legitimate tactics when used wisely by skilled managers, but others are way too much risk for the average investor. A big yield is a sign that it has crossed the line.

Let's examine the techniques to boost yield so you will know what to look for. Be sure to read our analysis on each fund for a more complete discussion of risk and strategy.

Leverage On its face, this is straightforward. Funds can borrow up to 30% of assets, and of course that boosts yield (and fee income) by 30%, too. Closed-end funds are much more likely to use leverage, because they can issue preferred shares to fund their borrowing. But even open-end funds can go beyond that limit because some financial instruments have built-in leverage.

Leverage can also be a warning sign about liquidity problems, as funds under the gun sometimes borrow in order to meet redemptions. Occasional use in bank-loan funds isn't such a bad idea because bank loans are slow to settle, but it is still a sign that things are being run without much slack. More-conservative bank-loan funds make sure to hold enough in cash and cashlike instruments so that they don't have to borrow.

Liquidity Mutual funds require daily liquidity: Investors can buy or sell any day that markets are open and are entitled to a fair price reflecting the portfolio's value at end of day. That's a piece of cake for large-cap equities and Treasuries, which trade in such volumes that it's quite easy for a fund to buy or sell all it needs in a day or two. But some bonds rarely trade because they are fairly small issues and may not have much published research on them. When credit markets turn stormy, these bonds can be hard to sell without taking sharp losses.

This is true particularly among small high-yield issues and nonrated muni bonds. In the credit crunch, however, many once-liquid bonds, such as mortgages not backed by the government, saw their liquidity disappear.

Third Avenue Focused Credit TFCIX is a more recent example of how this can go wrong. Most high-yield funds focus primarily on bonds that are expected to pay in full, issued by borrowers who are current on their principal and interest payments. In contrast, this fund invested heavily in distressed names, with the portfolio dominated by nonrated fare and bonds rated below B. It was also willing to hold large positions in individual names. In short, it was pushing the limits of what an open-end fund with daily liquidity would do, and it got burned. As the high-yield market was hit hard in late 2015 thanks to a sharp drop in energy prices, its performance cratered. When redemptions surged, the fund announced it wouldn't be able to meet them. It is only now wrapping up the unwinding of its holdings. Fortunately, very few funds push the boundaries as much as this one.

Return of Capital This is an old-school way to boost income. You take an investor's money, and you give it back to them so that they think it is yield when it isn't. A checking account would be better because you wouldn't be paying someone 90 basis points to do it. For the most part, this practice has gone away, but it still pops up, mainly in closed-end funds and Gabelli funds. While this practice doesn't increase the risk of a loss, it does erode principal so that, in dollar terms, your income will not keep pace with that of a fund actually generating an equal yield.

Interest-Rate Risk This one is pretty simple. A fund buys longer-dated bonds, and it can get a little more yield. Duration provides a good measure of a fund's interest-rate risk. I would caution, though, that interest rates have declined for so long that it's easy to miss the fact that a fund is packing a lot of interest-rate risk.

Credit Risk This is by far the most common way to boost yield, but it isn't as easy to spot as interest-rate risk. Big doses of credit risk, which also often come hand in hand with less liquidity, can actually mute volatility, and there isn't one simple measure like duration that captures how much credit risk a fund is taking. However, yield is a pretty clear indicator here. The median high-yield fund has a 30-day (SEC) yield of 4.5%, but some funds have yields well north of 6%.

It's been a long time since our last credit meltdown, so it's easy to miss just how much an aggressive high-yield fund can lose. Highland Opportunistic Credit HNRZX has an enticing 7.5% yield, for example, but it lost about half its value in 2008 and was down 26% in 2015. But credit risk is something we see in nearly every bond category, as managers will seek to boost returns in even the most mundane-sounding funds.

Issue Risk As I mentioned, most bond funds are very diversified by issuer because most bond-fund investors want steady performance as well as daily liquidity. When funds do allow big weightings of 4% or more, especially in bonds with more credit risk, their returns can be lumpier and an individual default can result in considerable pain. You can check a fund's issue risk level by looking at the largest bond positions and the total number of holdings. It's not a perfect system, though, because a fund will often own more than one bond from some issuers.

Some of our favorite and least favorite bond funds illustrate the differences between the good kind of aggressiveness and the bad.

Negative-rated

We don't cover Fairholme Focused Income FOCIX anymore, but it's interesting for having perhaps the most issue risk of any bond fund, with 10% in Sears debt, 10% in Imperial Metals debt, 12% in Seritage Growth Properties (Sears' REIT spin-off), and a bunch in Fannie and Freddie preferreds. On the plus side, Bruce Berkowitz does at least protect a bit against liquidity problems by having 26% in cash.

Negative-rated

Finally,

Smart Risk-Taking As I mentioned, funds can use most of the above risks well. For individual investors to make the most of these higher-risk funds, it helps to have a core of lower-risk high-quality funds that will enable you to sleep at night in times of crisis. One must also understand the risks involved, as all of these funds will take it on the chin at some time. Even looking down the line at past calendar-year returns will help you to get some idea of the downside.

Gold-rated

Gold-rated

Bronze-rated

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/fcc1768d-a037-447d-8b7d-b44a20e0fcf2.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/fcc1768d-a037-447d-8b7d-b44a20e0fcf2.jpg)