Hedging Currency Risk Comes With Costs

Before choosing a currency-hedged foreign-stock fund, it's important to understand the mechanics of hedging and the various outcomes that can occur.

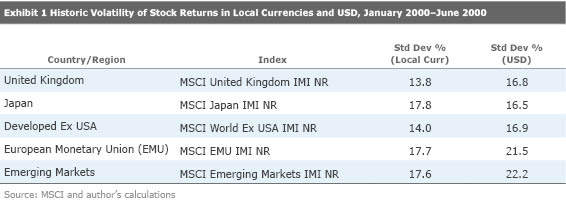

One of the drawbacks that comes with investing in foreign stocks is their higher volatility relative to domestic stocks. From January 2000 through June 2017, a U.S.-based investor holding a fund that simply tracked the MSCI United Kingdom Index weathered a standard deviation of 16.8%. That investor's counterpart in London, who owned shares in a similar fund, tracking the same index, experienced a standard deviation of only 13.8% during the same period.

Same index, but different volatility? There's some nuance here. The U.S. and U.K. indexes are not exactly the same. The former is denominated in dollars, the latter in pounds. And the source of the extra volatility borne by the U.S. investor was a direct result of fluctuating foreign exchange rates.

Foreign exchange rates are hardly static. Their fluctuations will--in most cases--increase the volatility of a U.S. investor's foreign stock portfolio. Exchange rates also tend to be cyclical and have little impact on long-term rates of return. Thus, over a long horizon, investors should assume that they won't be compensated for assuming currency risk.

This may sound troubling. Why take this risk if you're not going to earn anything in return? But not to fear, fund providers have come up with a solution: funds that hedge or eliminate this additional currency risk. But before choosing to pursue a currency-hedged fund, it's important to understand the mechanics of this activity and the various outcomes that can occur. Currency-hedged funds also have additional costs associated with them, which can make them more expensive than those that are unhedged.

The Mechanics of Foreign Exchange Volatility Exhibit 1 summarizes the volatility of foreign stocks from several regions denominated in their local currency and U.S. dollars. Indeed, there is ample evidence to support the idea that the returns of foreign stocks are more volatile when converted to U.S. dollars. The exception to this rule has been stocks listed in Japan, which were actually less volatile in dollars than yen.

Japanese stocks present an interesting and wonderful example when it comes to understanding how foreign exchange rates impact the volatility of foreign stocks. Effectively what is taking place here is the summation of the standard deviation of two signals. In this case the signals of interest are foreign stock returns denominated in local currency and a foreign exchange rate. The following equation relates the standard deviation of foreign stock returns in U.S. dollars (SUSD) to the standard deviation of foreign stock returns in local currency (SLCL) and a foreign exchange rate (FX).

This formula may look intimidating, but it essentially boils down to three components:

- The standard deviation of foreign stock returns denominated in local currency,

- The standard deviation of changes in the foreign exchange rate, and

- The correlation between foreign stock returns and changes in the foreign exchange rate.

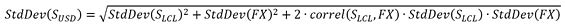

The third item, the correlation or relationship between the prior two, is less obvious but no less important. I'll illustrate this with a few hypothetical scenarios. First, let's assume that foreign stock returns in local currency have a volatility of 20%, and the exchange rate has a volatility of 10%. Now, let's keep these two values fixed and then alter the correlation, or the relationship between the other two variables. In the table below, I've plugged in three different values for the correlation coefficient: a value of 1 to illustrate a scenario in which stocks in local currency and exchange rates move in lock step, a value of 0 to represent a case where they have no relationship, and a value of negative 1 to reflect an instance where they move in opposite directions.

The results outlined in Exhibit 2 are extreme examples, but they demonstrate that the relationship between foreign exchange rates and local stock returns can have a significant effect on dollar-denominated returns. This shouldn't come as much of a surprise. Investors that understand the benefits of diversification know that uncorrelated assets can help reduce the volatility of a portfolio. In the same way, a negative correlation between local stock returns and foreign exchange rates causes the dollar-denominated standard deviation to be lower than that observed in local currency.

We can use the example of Japanese stocks to test this conclusion. Yen-denominated stock returns, as measured by the MSCI Japan Investable Market Index, had a standard deviation of 17.8%, and the standard deviation of the exchange rate between the dollar and yen was 8.2% from January 2000 through June 2017. During this span, the correlation between the two was negative 0.35. Throwing these numbers into the equation above results in a dollar-denominated volatility of 16.9%. It's not a perfect match, but pretty close to the 16.5% calculated directly from the dollar-denominated index. The mild difference between the two was attributable to differences in how the exchange rate data was treated. The monthly data I used was taken from the Federal Reserve Database, where the monthly index was calculated by averaging daily values. The MSCI index was calculated daily and didn't suffer from this approximation.

Hedging and Costs This observation has some implications on investment strategies that hedge away currency risk. Hedging currency risk effectively reduces the impact of foreign exchange rates. In most cases this reduces volatility. However, as Japanese stocks have demonstrated, hedging can actually increase volatility if stock returns and foreign exchange rates are negatively related. While this is certainly a possibility, it doesn't create a compelling argument to avoid strategies that hedge. Japanese stocks have been more exception than rule.

A stronger argument against currency-hedged strategies revolves around the costs involved with their execution. The costs of hedging foreign developed markets like Japan are typically small, roughly a few basis points on average. But these costs increase dramatically, into the 10-40 basis point range, for diversified emerging markets.[1] Some individual emerging markets can actually cost whole percentage points on an annual basis, depending on the currency and market conditions.

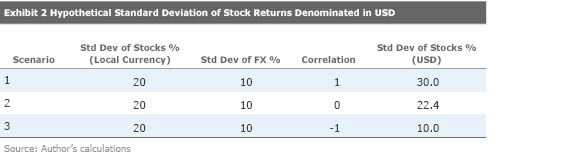

Currency-hedged strategies can also create a tax burden for investors, including those that use currency-hedged ETFs. Hedged strategies are typically executed with monthly forward contracts, which must be rolled over at the end of each month. This process can trigger short-term capital gains when profitable contracts are sold, but these contracts can't be purged from the ETF on an in-kind basis like stocks or bonds. Thus, ETF investors are on the hook for taxable gains triggered by hedging activity. Exhibit 3 summarizes the per-share capital gains distributions as a percentage of net asset value made between 2014 and 2016 on hedged and unhedged funds from BlackRock.

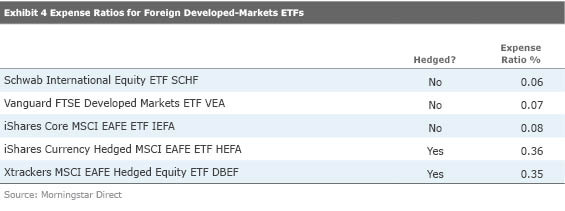

It's also worth mentioning the expense ratios of currency-hedged strategies tend to be higher than the lowest-cost funds in a given Morningstar Category. Foreign developed-markets funds are an easy example to pick on, and Exhibit 4 highlights several hedged funds along with a few low-cost unhedged options. The decision to hedge currency risk ultimately boils down to weighing costs against benefits. Currency-hedged funds provide the benefit of lower volatility but can be more expensive and create tax obligations when used in a taxable account. From an expense ratio perspective, the examples in Exhibit 4 have hedged funds charging about 30 basis points more on an annual basis in the foreign large-blend category.

[1] Hedging currency risk becomes costly when the forward exchange rate between two currencies is lower than the spot exchange rate. Rolling or selling forward contracts under this condition results in a loss. This condition occurs when a foreign interest rate is higher than the U.S. interest rate. The cost of hedging increases as the difference between foreign and U.S. interest rates increases.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)