Risks and Opportunities in Senior Loan ETFs

These investments offer attractive yields and can hold up well when interest rates rise, but they come with considerable credit and liquidity risk.

The article was published in the March 2016 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of Morningstar ETFInvestor by visiting the website.

Bond investors should expect no free lunches. Higher yields are almost always compensation for greater risk, whether that risk is apparent or not. The potential of rising interest rates is a meaningful risk that could create a headwind for bond investors. Investors could reduce their exposure to this risk by shifting assets to short-duration bonds. But conventional short-term bonds tend to offer lower yields than their longer duration counterparts. Substituting credit risk for interest-rate risk is a potential solution that may allow investors to earn higher returns. Senior loans (also called bank loans and leveraged loans) do just that.

A senior loan is a private loan that a firm takes out from a bank or a syndicate of lenders. These loans are backed by borrowers’ assets, which serve as collateral. In the event of a default, the lenders have a senior claim on the firm’s assets, meaning that they get paid before other creditors. That’s good, because almost all rated senior loan borrowers have below-investment-grade credit ratings.

Senior loans are appealing to low-credit-quality borrowers for a few reasons. First, this source of financing allows them to borrow at lower interest rates than they could in the bond or unsecured bank-loan market. Borrowers can also customize senior loans, repay them early with little or no penalty, and keep sensitive information private. In fact, borrowers have the right to reject the transfer of a loan outside the original syndication group. More-creditworthy borrowers tend to prefer unsecured bank and bond market financing because it can be costly to tie up assets in a loan. Senior loans may also have more restrictive covenants.

Default rates on senior loans have historically been slightly lower than those for high-yield bonds. This is because it is generally more difficult for these borrowers to restructure their debt and experience a technical default (that is, one not triggered by a payment shortfall). From 1998 through 2015, the average default rate on senior secured loans was 3.2%, based on the S&P LSTA Leveraged Loan Index. The corresponding figure for high-yield bonds was 4.6%. Additionally, defaulted senior loans have higher recovery rates because of their seniority in the capital structure. From 1998 through 2015, the weighted average recovery rate for senior loans was 80.1%, while the recovery rate on high-yield bonds ranged from 26.8% to 41.1%, according to data from S&P Capital IQ LossStats & LCD reported by the Loan Syndications and Trading Association. So while these loans have considerable credit risk, senior loans have tended to expose investors to smaller credit losses than high-yield bonds.

Almost all senior loans have a floating interest rate, which changes with market rates. They typically pay a fixed spread over a benchmark rate, such as Libor, often subject to a floor (for more information on interest-rate floors, please see "Why Yields on Floating-Rate Bank Loans Aren't Floating ... Yet" in the June 2015 issue of ETFInvestor). These rates usually reset once a quarter, which gives senior loans very a short duration and mitigates the impact of fluctuating interest rates on their prices. This, together with high recovery rates and borrowers' prepayment option, mitigates these loans' deviations from par value.

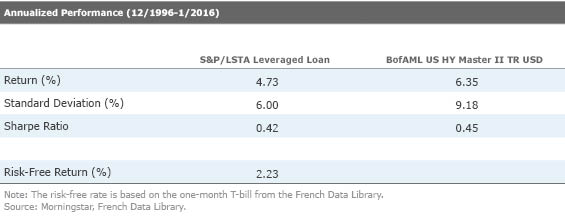

From December 1996 through January 2016, the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan 100 Index exhibited about two thirds the volatility of the Bank of America Merrill Lynch U.S. High Yield Master II Index. However, the leveraged loan index fared slightly worse from a risk/reward perspective, as evidenced by its Sharpe ratio in the accompanying table.

Liquidity Challenges Senior loans sound like a good deal. They have historically had lower credit losses than high-yield bonds, less interest-rate risk than intermediate-term, fixed-rate bonds, and higher yields than many other short-duration instruments. But it is important to bear in mind that these high yields are compensation for risk. In addition to their credit risk, these loans carry considerable liquidity risk.

Senior loan originators can sell their portion of the loan to other investors on the secondary market. Unlike traditional bonds, these loans do not settle on a T+3 schedule (three days after the transaction date). In fact, there is no maximum settlement period for these loans, though the median settlement period in the first three quarters of 2015 was 12 days according to the LSTA. That can pose a challenge to funds that provide daily liquidity such as mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

Funds generally have four options to manage this liquidity risk:

1) Hold a portion of their portfolios in cash, high-yield bonds, or other securities with T+3 settlement.

This is one of the strongest lines of defense. Cash and liquid securities offer a buffer to help senior loan funds meet redemptions, but these holdings dilute exposure to senior loans.

2) Stick to the most liquid senior loans.

Settlement times for these loans tend to be shorter.

3) Request accelerated loan settlement.

Counterparties are not required to offer accelerated settlement, though the many of these funds’ managers indicate that their counterparts are usually willing to accommodate their requests for accelerated settlement.

4) Establish an emergency line of credit.

If all else fails, a line of credit can give a fund the cash it needs to meet investors’ daily liquidity needs while it is waiting for the sale of its underlying loans to settle.

Together, these lines of defense should enable managers to provide daily liquidity, even in periods of market stress, but they don’t entirely eliminate liquidity risk. Senior loans are generally less heavily traded than bonds. If a manager wants to sell a loan, it may take longer to find a buyer and he may have to accept a lower price to make the transaction happen. Therefore, it can be expensive to demand liquidity in this market.

Senior Loan ETFs

In light of the liquidity challenges senior loans face, an ETF wrapper may not seem like a suitable vehicle for investing in them. In fact, BlackRock has cited liquidity challenges as a key reason not to launch a senior loan ETF. Despite these challenges, there are currently four senior loan ETFs:

Indexing illiquid assets can result in high transaction costs, as index changes create liquidity-demanding trades that can push loan prices away from index fund managers. In order to mitigate this potential problem, BKLN (by far the biggest senior loan ETF) tracks the S&P/LSTA U.S. Leveraged Loan 100 Index, which targets the 100 largest senior loans and weights them by market value. These are among the market’s most liquid senior loans. While the index’s design improves the fund’s overall liquidity profile, it could also skew the portfolio toward the most heavily indebted borrowers. Invesco (PowerShares’ parent company) subadvises the fund. The management team, led by Scott Baskind, is willing to accept some tracking error to manage liquidity risk. They generally keep 8%-9% of the portfolio in cash and 7%-9% in high-yield bonds with T+3 settlement. Where possible, it targets the bonds of issuers in the index.

SNLN’s index directly screens for the 100 most liquid senior loans, which it weights by market value. But it tends to have considerable overlap with BKLN. As of Jan. 27, 2016, their common holdings accounted for 64% of SNLN’s portfolio. Unlike BKLN, SNLN does not hold any high-yield bonds. It does, however, currently have a 10% cash stake, according to Morningstar data.

Active management is probably a better way to go in the bank-loan asset class, as it may allow for better liquidity and credit risk management. And the cost difference between the index and active strategies is fairly small. SRLN and FTSL both have capable management teams. But of the two, I prefer SRLN because of its lower fee and GSO’s leading position in the senior loan market.

Blackstone/GSO subadvises SRLN. GSO is one of the largest senior loan asset managers in the world. Dan McMullen is the lead manager on the strategy, and he is supported by a team of 19 credit analysts. They attempt to identify mispriced loans through bottom-up credit analysis, trying to catch things that the ratings agencies miss. The managers may layer on some top-down positioning to manage risk. Unlike their ETF peers, they are able to take advantage of opportunities in the primary market, which may improve their odds of finding undervalued loans. Qualifying loans must have at least $250 million outstanding, which helps improve liquidity. The managers generally keep around 2% of the portfolio in cash (that figure is currently around 5%) and 8% to 10% in high-yield bonds to further manage the fund’s liquidity needs.

The managers of FTSL also attempt to outperform through fundamental credit analysis. Lead manager Bill Housey and his team of analysts look for issuers with stable cash flow, strong management teams, and quality assets (as do many of their peers). They share GSO’s view that the ratings agencies are slow to pick up on new information, which can create mispricing that the managers can exploit. This team screens loans for liquidity and makes lots of small bets, to reduce liquidity needs from any individual holding. Cash and high-yield bonds typically account for around 20% of the portfolio.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc.'s Investment Management division licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/09-25-2023/t_f3a19a3382db4855b642d8e3207aba10_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)