Have Long-Short Credit Funds Delivered?

Implementation challenges, poor performance, and high costs weigh heavily on this Morningstar Category.

In May, Morningstar spun out a small subset of non-traditional-bond funds that focus on corporate credit into a new long-short credit category (currently 21 funds totaling roughly $11 billion in assets). Long-short credit funds sound interesting in theory. Corporate credit markets are rife with inefficiency, and a long-short strategy that seeks to benefit from anomalies in the pricing of credit risk while minimizing exposure to broader credit and interest-rate market swings may sound enticing--especially in overvalued (2013) and volatile credit markets (2015).

In practice, though, the strategy has struggled to deliver, both for the hedge funds that have greater flexibility with which to execute it and the highly regulated open-end mutual funds that try to adapt it to structures that permit investors to redeem assets at any time of their choosing. The long-short credit Morningstar Category may be a newly assembled group, but we don't expect its popularity to take off anytime soon. Implementation challenges, poor performance, and high costs damage the group's overall appeal.

As with the non-traditional-bond group, these funds typically have absolute return targets of Libor plus a spread of between 300 and 600 basis points, with the intention of producing mid-single-digit annualized returns. Unlike the non-traditional-bond group, however, many funds in the long-short credit category attempt to take bets on the direction of interest rates out of the equation by hedging out their interest-rate sensitivity to focus on extracting value from their corporate trades. Those trades may include directional long and short bets on over- or undervalued corporate debt, or relative-value trades. The latter could include exploiting divergence in the pricing of cash bonds and derivatives markets, betting that one security in a company's capital structure is undervalued versus another, or pair-trading between the debt of two different but correlated companies.

These can be difficult strategies to pull off successfully, even for hedge funds, which have more flexibility to control the timing of investor redemptions than mutual funds. Given the fluctuating here-today-gone-tomorrow nature of liquidity in the corporate-bond market, even relative-value trades between closely linked securities can court significant basis risk that can cause volatility when pricing relationships move in unexpected ways. Timing can also be tricky when shorting bonds. If a manager is too early, a fund will lose money paying out income on the bonds it has borrowed until a trade succeeds. If a manager waits too long, the cost of borrowing the bonds for shorting could overwhelm the value of the trade. Although the evolution of derivatives markets has given managers more liquid instruments to work with, strategies that rely heavily on trading can still find it difficult to source and sell bonds at optimal times.

Hedge funds that aim to minimize systematic credit market exposure, or beta, tend to stick to a relative value approach. Because the expected gains from individual trades are typically small, it's not unusual to see pure relative-value credit hedge funds apply leverage of 3 times or more in order to target returns in a more salable high-single-digit range. Leverage is a two-edged sword, of course, magnifying returns when the execution is successful but amplifying losses when bets go badly.

Credit hedge fund strategies that don't take on a lot of leverage may lean more heavily on directional bets, often among higher-yielding stressed issuers for which they believe their fundamental research gives them an edge. That, in turn, exposes the fund to more event risk--the risk that downgrades, defaults, or bankruptcies will trigger a sudden sell-off--in which losses are typically larger than potential gains (that is, negative skewness), and broader market risk as well.

Neither approach represents an easy path to riches, and both of these strategies are inherently problematic for their mutual fund adopters. For one, mutual funds are limited in the amount of leverage they can use, which is an important risk-management guardrail but makes it hard to get much oomph from a pure relative-value strategy. For funds that lean more heavily on directional (mainly long) trades, the liquidity risk associated with investing in lower-credit-quality tiers is a potential danger. Indeed, of the funds that report credit-quality breakdowns in their literature, exposures to junk-rated bonds can take up half or more of a portfolio. Several also include significant exposure to bonds rated CCC or below, with some plunking as much as a third of assets in CCC rated fare (compared with 15% of the Barclays U.S. Corporate High Yield Index).

Meanwhile, credit hedge funds typically lock up investor capital for at least a quarter, and those that focus mainly on distressed investing often won't allow redemptions more frequently than once a year, with many employing gating mechanisms that return capital to investors gradually. Those terms help prevent hedge funds from having to sell less-liquid instruments in an inhospitable market environment if investors suddenly want their money back. Mutual funds that invest in stressed and distressed issues enjoy no such safeguards, a lesson that Third Avenue Focused Credit crystallized in 2015.

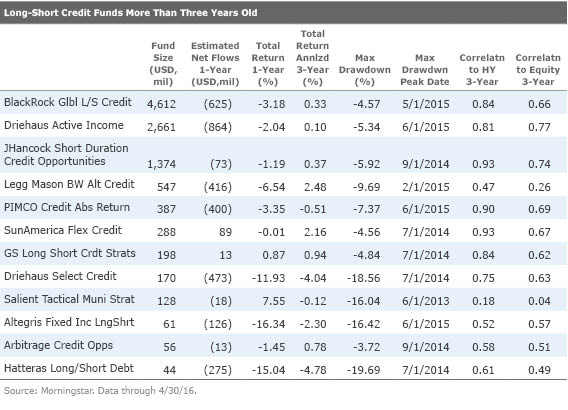

The downside of these funds' appetite for credit risk has been on display during the past year, as fundamental cracks in energy and other commodity-related industries caused tumult in the high-yield market, as shown in the following table.

Many long-short credit investors are losing patience. Steady net outflows from this cohort since September 2014 reached $5.6 billion as of April 2016, a sizable decline from the group's peak asset base of $18 billion in July 2014. Most funds that have been launched in the past couple of years have fared no better than those listed above, and early blemishes on their performance records won't make it any easier for them to raise assets.

Long-short credit investing is difficult under the best of circumstances. Pulling it off successfully within the constraints of the Investment Act of 1940 open-end mutual fund structure is even more difficult. With the added impediment of steep price tags starting in excess of 1.00% per year for most institutional share classes, it's hard to make a case for these funds.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NOBU6DPVYRBQPCDFK3WJ45RH3Q.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)