Economic Outlook: More Slow Growth but Labor Scarcity

U.S. real GDP growth in 2015 will likely fall in the 2.0%-2.5% range yet again, but labor tightness is building.

- U.S. economic growth is likely to remain lower than many believe, at 2.0% to 2.5%, but high enough to create labor market shortages.

- The quarter's notable developments were the ECB quantitative easing program (which resulted in a sharply falling euro), weaker growth in China, bad weather (again), and slowing U.S. exports.

- Threats of labor scarcity are building, helping consumers but potentially sparking higher inflation and lower corporate profits.

Our economic outlook in 2015 remains relatively unchanged from our last report, with U.S. real GDP growth likely to fall in the 2.0%-2.5% range for the fourth year in a row.

As usual, consumers, who constitute 70% of GDP, will be the biggest drivers of that growth rate. Higher incomes and employment rates could push consumption slightly higher than in 2014, when consumption grew 2.5%. Residential spending, which grew a paltry 1.6% for all of 2014, should do quite a bit better in 2015, although weather has caused this sector to get off to a slow start for the year.

Business investments grew about 6% in 2014 and will probably do about the same to slightly worse in 2015, as oil-related capital spending goes down, and most structures, excluding distribution centers, remain under pressure. Net exports were a detractor from GDP in 2014, as export growth slowed with both weak business conditions and a soaring dollar. The best case would seem to be that the negative impact of net exports doesn't get any worse in 2015. But more likely, net exports will be a slightly bigger detractor. Government was a very, very smaller detractor from GDP growth in 2014 and will probably add modestly to 2015's growth.

First Quarter Review: Consensus Growth Estimates Reduced as Energy Downside Intensifies The general thinking at the end of the fourth quarter was that as gasoline prices came down, consumers would spend more and drive the economy up to escape velocity, with the consensus forecast for 2015 well over 3%. Most of those forecasts have now dropped closer to our forecast of 2.0% to 2.5% growth.

Weather effects, some of which can never be made up for (think restaurant meals, airline seats, etc.), are certainly part of the explanation of why growth has slowed. The other part of the consensus reduction is the realization that falling energy prices are not a one-way street. Yes, cheaper gasoline puts more money in consumers' pockets to buy other things. However, consider all those workers in North Dakota, Texas, and other oil-producing regions, who may be worried about or may have even already lost their jobs. Real estate market activity is already off 10%-15% in the Houston area. And don't forget about all the capital equipment that goes into oil fields. We have long contended that much of the unexpected strength in the manufacturing sector was related to the activity in the oil patch. Computers, drill bits, tubular steel, even manufactured housing (to temporarily house oil field workers) all saw at least some benefit from rapidly growing oil production and could now feel the pain.

Strong Dollar Slows Exports The strong dollar, now up over 20% on a trade-weighted basis, also has the potential for reducing U.S. exports. A stronger dollar means that U.S. goods are more expensive and less competitive overseas. For years we have argued that with exports just a meager 13% of GDP, export weakness wouldn't make much of a difference to U.S. GDP growth. However, with the U.S. economy stuck at a 2.0% to 2.5% growth rate, even a few tenths of a percent reduction in exports begins to weigh on overall growth rates. However, exports shouldn't fall enough to badly damage the economy or throw the U.S. into a recession.

Europe Gets Advantage of QE Before the First Bond Was Bought Also in the first quarter, the European Central Bank rolled out its quantitative easing measures with a bang, announcing a bond-buying program that will likely top the $1 trillion mark, roughly matching the size of the U.S. QE 3 program. Europe should do better in 2015 with that QE program, which should keep the euro weak, and support exports and cheaper interest rates, encouraging more lending. Throw in cheaper energy prices, and Europe will find it hard not to do at least a little better in 2015. However, without some hard choices and structural reforms, the stronger European economy might not last long.

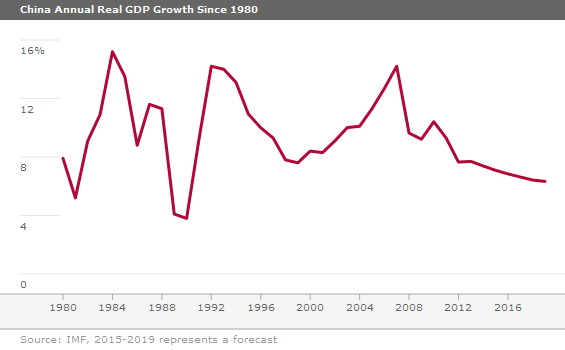

China's Growth Rate Is Not Coming Back The world is also finally coming around to the fact that China is not ever returning to the "good old days" of 10%-12% GDP growth rates. Current forecasts are for growth of around 7% in 2015, down modestly from 7.4% in 2014. Five years from now, we believe that China might be growing at under a 5% rate due to demographics, slowing real estate markets, and the continuing transition of the economy from investment to consumption. That projection is probably a bit more dour than the consensus forecasts, but if correct, if will keep a lid on many commodities and could weigh on miners, manufacturers, and other emerging-markets economies, at least in the short run. However, the worst of the downward thrust in commodity prices may be behind us.

Put Wage Inflation on the Radar We have discussed the potential trends of slower population growth and a declining labor pool in previous quarterly columns. This quarter, we are broadening our analysis to show the potential impacts of these trends on inflation and corporate profit margins. These are not meant to be a detailed roadmap or forecast. Instead, we are trying to open investors' eyes to the fact that even as falling oil prices have most economists worrying about deflation, the seeds for the next round of inflation are already in place, with broad implications for corporate profits. Greater corporate investments in productivity-enhancing technologies and changing worker behaviors (working later in life, for example) could potentially derail our labor scarcity and lower-profit-margin theories. The U.S. economy in particular has proven very resilient and adaptable over the years.

For the last year we have talked extensively about demographics and how they are likely to keep a lid on long-term growth. That continues to take its toll on economic data, as U.S. population growth has slowed from 1.8% in the 1950s to 0.7% currently, and is on its way to 0.5% over the next couple of decades. Population growth, along with productivity changes, are the two key variables in determining economic growth. Therefore, economic growth over the next several decades will be restrained by the population growth reality. This is also a fact for most of the rest of the world, especially the developed world.

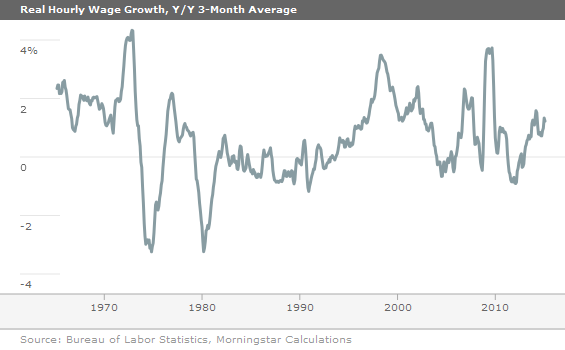

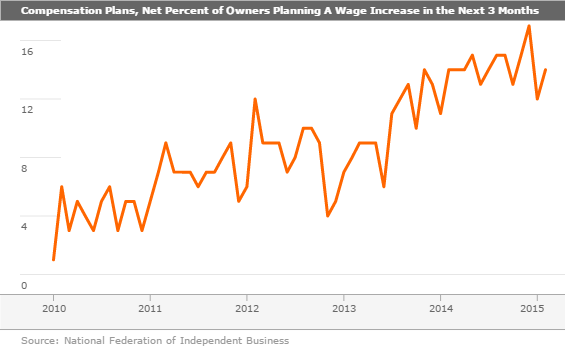

The labor scarcity issue is finally beginning to turn up in 2015. Recall that the number of U.S. born residents between ages 22 and 62 will decline for the first time in 2015 after adding well over a million workers per year at the turn of the century. Falling unemployment rates, soaring job openings, and falling initial unemployment are showing an economy moving toward full employment. Although not exactly lighting the world on fire, inflation-adjusted wage growth has improved in a straight line from negative 0.3% in 2011 to 1.2% in February (on a three-month moving average year-over-year basis), except for a weather-related dip in early 2014. That may not sound like a lot, but real wages have only grown at a 0.7% compound annual rate over the last 50 years, in a range of -3% to +4%.

In addition, the labor market data would suggest that wages are due for even more growth over the next decade. In previous reports, we have cited regional airline pilots, dry wall installers, and truckers as groups that are already seeing shortage issues and have had to boost pay accordingly. Now other employers are also reporting that they are planning to boost wages. In the retail sector alone,

Two-tier wage schemes that have pressured wages over the past several years are coming under pressure, too. The Wall Street Journal reports that the auto unions are seeking to eliminate or phase down the two-tier wage structure that has been in place in the auto industry since 2007. Veteran auto workers have maintained their relatively high $28 hourly wage rate while new workers are generally hired at $19 per hour, according to The Wall Street Journal.

While it's doubtful the two-tier system will be completely scrapped, it's relatively likely that union workers will begin to make a dent in the corrosive system in their quadrennial labor negotiation, in our opinion.

Wage Growth Good News for Consumers and Companies That Serve Them, Not Great News for Profits The potential wage growth will likely be good news for consumers, who should be able to extract higher wages out of corporations. It will also be good news for corporations that serve the middle markets (higher incomes should increase spending) and have relatively low labor content.

The downside is that wages are a very important part of corporate cost structures, and rising wages will likely impact corporate profits, especially for companies without economic moats that won't be able to pass along the wage increases.

The empirical link between wages and profit growth is a bit sketchy because there have been only three or four bouts of sharply rising inflation-adjusted hourly wage rates in the last 50 years. The 1970s saw large wage gains, and that period was generally associated with deteriorating corporate earnings, but there were a lot of other concurrent factors depressing profits. The most damaging demonstration of rising real wages and falling profits was the late 1990s when true labor shortages developed, and wages soared. It was one of the very few periods when wages soared and other economic conditions were rather benign, and profits fell. Wages spiked again in 2005 and 2006, which was followed by falling profits in 2007 and 2008. Again, the profit decline of 2007 and 2008 had a lot of other causes, including the tumbling housing market.

Rising Wage Rates Plus a Quickly Narrowing Output Gap Could Pressure Inflation by 2017 The other bad news relative to higher wage growth is that it will put upward pressure on the inflation rate. In fact, the Fed is most likely to tighten credit if wage growth gets too high in order to avoid a wage price spiral.

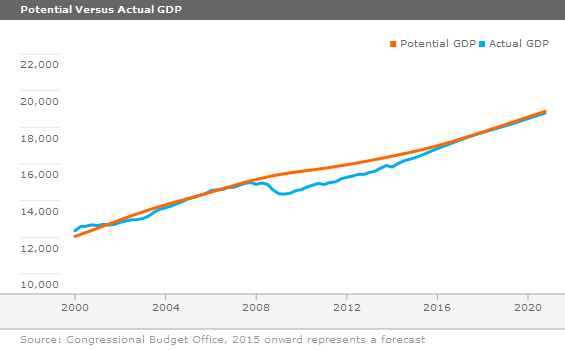

The worry becomes a little more real in the years ahead as the economy approaches full capacity. Data from the Congressional Budget Office suggests that, based on its broadest measures of capacity (including labor, capital, and productivity), the economy will be at full capacity by 2017. If the economy grows faster than CBO is projecting, we could hit full capacity even sooner. In the past, as the economy has approached full capacity, inflation has accelerated sharply. That, in turn, bodes poorly for the economy another year or two down the line. As we have said before, inflation is the ultimate recovery killer.

Since 2008, the economy has been operating well below capacity. This has kept a lid on inflation, despite a very liberal Federal Reserve and occasional commodity price spikes in food and materials. At its widest point, in 2009, the output gap was over 7%, making it nearly impossible for any business to raise prices without fears that a competitor with excess capacity would refuse to follow suit. Currently that gap has narrowed to just over 2% and is expected to get very close to zero by 2017. That narrowing gap typically has caused acceleration in the rate of inflation. Still, another short-run recession, perhaps triggered by a geopolitical event or a terrorist attack, could push out this day of reckoning. We are not claiming higher inflation rates are a certainty, just that the probability for a higher inflation rate is much higher than many investors believe.

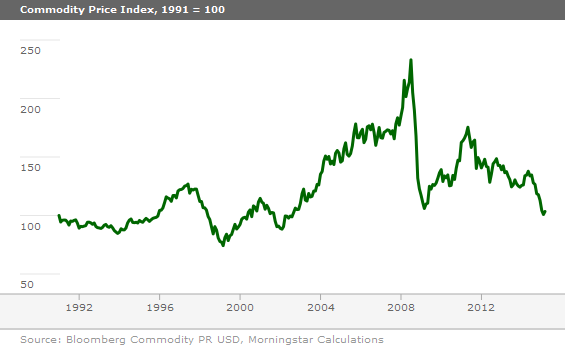

Commodity Prices Likely to Stop Dropping at Some Point Falling commodity prices have been one of the rare bright spots for the consumer over the course of this recovery. After a huge, above-trend move in commodity prices in the early 2000s, commodities in general have been trending down since 2009. The 2000s boom was likely due to China's fixed-investment-based economy, which drove up raw materials of all kinds. However, as that growth slowed and China became more efficient, some of the pressure came off.

The worldwide recession also contributed to the decline in commodities that began in 2009 with the great recession. As the economy improved and agricultural commodities and oil surged in 2011 on world instability, there was a brief spike in commodity prices. Since then, slowing world growth rates have caused at least one broad-based commodities index to drop back to 1990s levels.

Although we don't see any particular reason or have any idea when commodity prices might surge again, the possibility needs to be on everyone's radar screen. With the world population continuing to grow, albeit much more slowly, and supplies of commodities physically constrained, especially in the short run, the rout in commodities will end at some point, and we are already approaching previous lows in a number of commodity indexes.

Corporate Profit Margins Could Come Under Pressure At 7.2%, corporate profits as a percentage of gross domestic income are currently near all-time highs. Bears have been whining that profit margins have been unsustainable since at least 2010. We tended to ignore the dire warnings that the end was near and attributed the strong profit levels to a shift toward more service-oriented businesses (which have fewer ups and downs compared with manufacturers) and technology. To some extent, I still believe this is partially true. However, a recent article written by two CFAs, Baijnath Ramraika and Prashant Trivedi, on Advisor Perspectives (an interesting source, but not a peer-reviewed journal) suggests that other corporate-profit tailwinds could disappear in the future. According to Ramraika and Trivedi, low interest rates, low investment rates, and reduced SG&A expenditures due to short-termism by managers have been the primary drivers of higher profits, and not some wonderful productivity boom.

Some of our already-building worries due to higher wages and corporate profitability could be amplified by trends cited above. Higher inflation and a tighter Federal Reserve could push interest rates higher. Lower interest rates have been a key part of the profit improvement story, and while we can all argue about the exact timing of when interest rates will go up, there is little doubt that they will go up.

Also, with the output gap so wide, corporations haven't had to expend a lot of money on new capital equipment, which has kept down depreciation expenses. Now, especially with labor costs moving upward, corporations will likely need to expand their capital budgets. Creative accounting and the ability to recognize income in low-tax countries have also been part of the recent rise in corporate profits, despite relatively high and stable statutory rates for U.S. companies. Ramraika fears that there will be increasing pressure for corporations to pay more corporate taxes in the years ahead. Going forward, we don't think lower taxes are going to be as powerful a force in improving corporate margins as they have been over the last several years. And the situation could grow worse as the populist movement clamors for businesses to pay more of their share of taxes.

The profit bears have been crying wolf for an incredibly long time, and just as investors have learned to ignore them, they may have a shot at being right over the coming years. No guarantees, promises, or dates here, but it looks like the profit tide could begin to turn after an incredible run. The current run is matched only by the run between 1960 and 1965. Of course that ended very badly for profits and the stock market. With some of the pressures still a couple of years away, businesses and consumers may still adjust their plans to avoid the worst of the problems. Plus, the slower growth resulting from worsening demographics could also alleviate some of our margin and inflation worries.

More Quarter-End Insights

- Stock Market Outlook: Proceed With Caution

- Credit Outlook: Demand Rises for Higher-Yielding U.S. Dollar-Denominated Debt

- Basic Materials: China Will Keep a Lid on Most Commodities

- Consumer Cyclical Investors: Shop Carefully in 2015

- Consumer Defensive: Attractive Companies, Top-Shelf Valuations

- Energy: Coping With Lower Oil and Gas Prices

- Financial Services: Bank Worries Are Overdone

- Health Care: 3 Picks in a More Expensive Sector

- Industrials: A Few Bargains Still Remaining

- Real Estate: REITs That Can Weather a Rising Rate Environment

- Tech and Telecom Sectors: Time to Be Selective

- Utilities: Bloody February Brings Valuations Back In Line

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5GAX4GUZGFDARNXQRA7HR2YET4.jpg)